Principal Justin Endicott of Huff Consolidated School and Principal Katie Endicott of Westside High School engage with other leaders during a professional development session around the Model of Instruction for Deeper Learning, which is designed to build student and teacher agency.

By: Dr. Merewyn E. Lyons and Dr. Lindsay Elliott

One of the most powerful yet often overlooked drivers of student success is teacher agency. When educators are empowered to take ownership of their teaching practices, receive actionable feedback for professional growth, and collaborate meaningfully with their peers, the entire school thrives.

This article explores how education leaders at the district and school level can actively harness the power of teacher agency. As teachers develop higher levels of agency, they in turn empower their students to take ownership of their academics and behavior and develop high agency skills.

We cover research-based strategies that leaders can use to create this ripple effect across their school and district, increasing teacher retention while also improving student achievement, engagement, and behavior.

Why Teacher Agency Matters: Reversing the Decline in Teacher Retention

The National Center for Education Statistics (2023) reported that 86% of K-12 public schools in the United States had difficulty filling teaching positions for the 2023-2024 school year. In 2024, 50% of public-school leaders reported that their schools were understaffed (National Center for Education Statistics, 2024).

Some contributing factors to this shortage of teachers may be that perceptions of prestige and job satisfaction of the teaching profession are at the lowest level in 50 years (Kraft & Lyon, 2024). Although many factors influence this declining trend, there is strong evidence that a loss of agency is negatively affecting the willingness of people to enter or stay in teaching (Davis, 2024; Kraft & Lyon, 2024).

Leadership practices play an important role in reversing teacher attrition and making the teaching profession more attractive to prospective educators. The key is knowing how to support teachers’ basic psychological needs and build teacher agency.

The Three Basic Psychological Needs (BPN) and Why They Are Critical for Teacher Agency

At Instructional Empowerment’s Applied Research Center, we have analyzed the science behind how human motivations affect teaching practices, deeper student learning, and educational leadership.

We have grounded our work with schools and districts in self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017). This theory states that all human beings have three basic psychological needs (BPN): the need for autonomy, the need for competence, and the need for relatedness. Understanding these three human needs is critical for creating learning environments that foster student and teacher agency.

(1) Autonomy: Autonomy is volitional action towards a goal that people embrace as consistent with their sense of self and is integrated with their values and their sense of purpose (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2017, 2020). In other words, autonomy is choice and ownership.

(2) Competence: Competence is the feeling of being capable, knowledgeable, and skilled (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2017, 2020). People who feel competent derive satisfaction from successful completion of activities that allow them to demonstrate their abilities (Di Domenico & Ryan, 2017). In other words, competence is confidence in one’s own abilities.

(3) Relatedness: Relatedness is the sense of caring about others and being cared for by others (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2017, 2020). It provides a sense of security and belonging as a valued member of a group. In other words, relatedness is a sense of belonging.

How BPN Affects Student, Teacher, and Principal Outcomes

Leadership support of the three basic psychological needs (BPN) is essential to everyone at the school: students, teachers, and principals.

Student Outcomes

When BPN Is Fulfilled

The fulfillment of BPN is essential to developing student agency and resilience as learners (Reeve et al., 2020). Students who take responsibility for their learning, feel competent as learners, and who feel valued as part of a learning community (Gottfried et al., 2008) also:

- Feel good about themselves

- Have a positive attitude about their education

- Persist in the face of challenges

- Perform well academically

What Student BPN Fulfillment Looks Like: Example from the Field

Katie Endicott is the principal of Westside High School in Hanover, West Virginia. She and her school partnered with Instructional Empowerment to implement the Model of Instruction for Deeper Learning, which is designed to improve student outcomes and fulfills their BPN. Katie shared the positive change she sees in her students as they take ownership of their learning, become more confident, and feel a sense of belonging in their student-led teams.

“We are seeing student autonomy and ownership take place. I believe that’s been one of the most beneficial and powerful shifts that I’ve seen. Students now care about being in the classroom. They care about their learning. They understand that they are in a team, and in this room they are a facilitator, a team member, or a record keeper. They know that they have different roles in their teams and that every role is powerful. Every role is beneficial, and they feel like it matters. Their presence in the classroom matters because now they’re not just doing a worksheet that they can make up after they’ve missed three days. They’re actually part of a team, and they’re working together on a task.”

Katie Endicott

Principal, Westside High School, West Virginia

When BPN Is Thwarted

Students whose needs are thwarted by their experience of school do not experience volition in learning (Reeve et al., 2020). They lose motivation to learn and avoid tasks over which they have no opportunity to exercise choice or autonomy (Bartholomew et al., 2018). Students whose BPN are not fulfilled by their experience of school behave in maladaptive ways (Bartholomew et al., 2018; Collie et al., 2019; Filippello et al., 2017; Howard et al., 2021; Reeve, 2009; Ryan & Deci, 2017) such as:

- Learned helplessness

- Anxiety

- Absenteeism

- Oppositional behavior

Such behaviors set students up for a cycle of failure that will negatively impact the rest of their lives, limiting or blocking their opportunities for success and upward mobility. Teachers have a direct influence on the degree to which their students’ BPN are met. Their words and actions can convey messages of attentiveness or indifference to students’ interests, confidence or a lack of confidence in students’ abilities, acceptance or rejection of their students as part of the classroom community.

Teacher Outcomes

Teachers also have needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Basic need satisfaction explains both teacher job satisfaction and teacher commitment to professional learning (Jansen in de Wal et al., 2020).

When BPN Is Fulfilled

Teachers whose basic psychological needs are fulfilled (Ahn et al., 2021; Soenens et al., 2012; Basileo & Lyons 2024) are:

- More likely to support the basic psychological needs of their students

- More likely to successfully adopt innovations

When BPN Is Thwarted

When teachers’ BPN are not satisfied (Collie, 2021; Eyal & Roth, 2011), teachers experience:

- Stress

- Emotional exhaustion

- Burnout

Principal Outcomes

Principal leadership is essential to fulfilling teachers’ BPN; however, principals also have the same needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness as teachers and students.

When BPN Is Fulfilled

Satisfaction of principals’ needs (Ryan & Deci, 2017) and BPN support from their superintendents (Chang et al., 2015; Ryan & Deci, 2020) is associated with:

- Work commitment

- More affective commitment (emotional attachment) to their schools

- Higher job satisfaction

- Higher likelihood of supporting the BPN of teachers

When BPN Is Thwarted

For principals, frustration of their needs (Ryan & Deci, 2017) and lack of BPN support from their superintendents (Chang et al., 2015; Ryan & Deci, 2020) is associated with:

- Exhaustion

- Less affective commitment (emotional attachment) to their schools

- Lower job satisfaction

Subscribe for curated education insights delivered every two weeks.

Understanding the Connection Between BPN and Agency

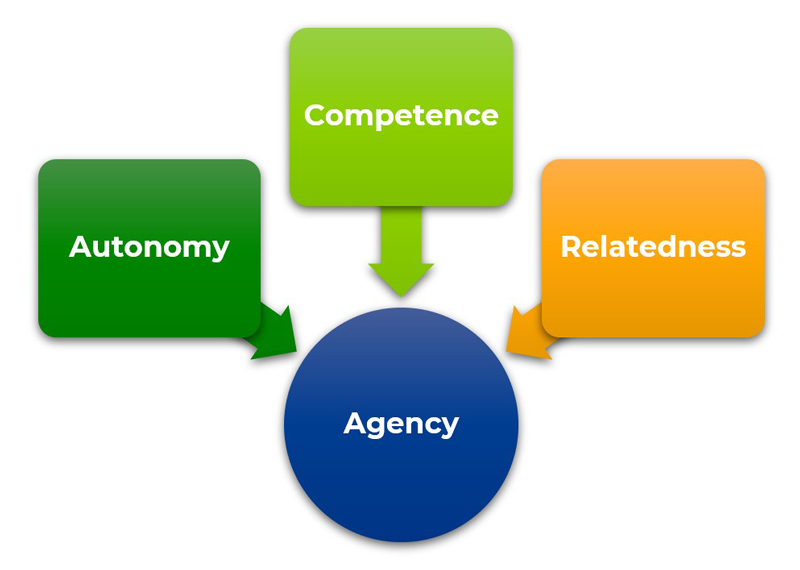

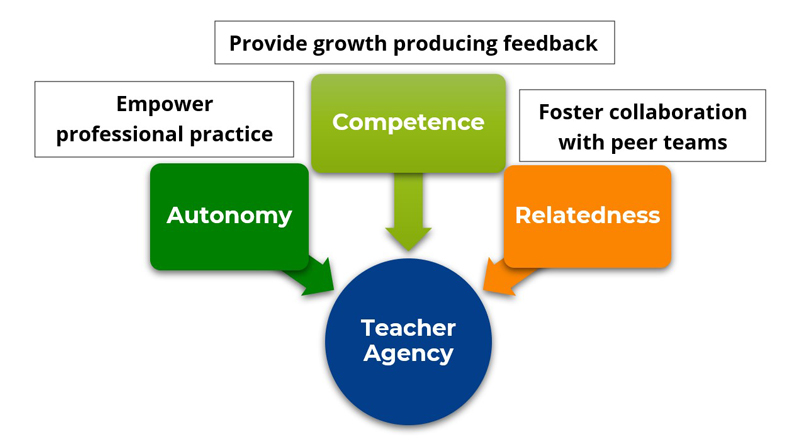

Agency is our ability to self-manage our thoughts and actions to make positive and meaningful changes in our lives and in the lives of others (Bandura, 2006). Students, teachers, and leaders all need to develop strong agency to perform at their highest levels. But agency will not flourish without the satisfaction of the three basic psychological needs (BPN). As discussed above, the fulfillment or thwarting of BPN has a drastic effect on student, teacher, and principal outcomes. Figure 1 depicts the relationship between BPN and agency.

Figure 1. The three basic psychological needs support the development of agency for students, teachers, and leaders.

Why Is Student Agency Important?

Instructional Empowerment’s mission is to end generational poverty and eliminate racial achievement gaps through redesigned rigorous Tier 1 instruction. Student agency is the key to achieving this mission.

People experiencing generational poverty are deprived of basic capabilities to live a life free of illness, undernourishment, and illiteracy and to access opportunities to live a full and meaningful life that provides for their needs and the needs of their families. To break the cycle of generational poverty, they must be free to develop agency to bring about change in their lives (Sen, 1999).

This agency development must begin in the first system that children encounter in their lives as they enter the world outside their own families – the educational system. Education is the means for students to attain freedom to purposefully use all their capabilities, express their true nature, and attain happiness (Ryan & Niemiec, 2009). It is only possible when students exercise agency as learners.

Through education, all students can develop the individual and collective agency they need to bring meaningful, positive change to their lives and the lives of others and to achieve upward mobility and career success.

Teaching Practices That Build Student Agency

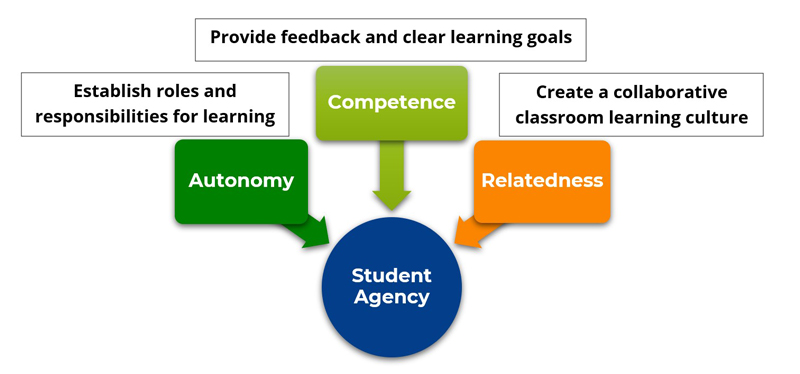

Teachers develop student agency by supporting students’ BPN (Figure 2). They can support student autonomy by providing roles and responsibilities for learning, build student competence through feedback and clear learning goals, and foster relatedness by creating a collaborative classroom learning culture.

- Establish roles and responsibilities for learning: Teachers provide learning opportunities with structured roles and responsibilities for students that progressively develop individual and collective skills of self-management and allow students to exercise greater control over their own learning.

- Provide feedback and clear learning goals: Teachers encourage students’ sense of competence by giving informational feedback and providing learning tasks with clear goals against which students can track their own progress and adapt their strategies to improve learning.

- Create a collaborative classroom learning culture: Teachers foster students’ feeling of relatedness by building a safe and collaborative culture in their classrooms where students work in teams to support each other’s growth as learners.

Figure 2. Teachers build student agency through meeting students’ needs.

How Agency Development Changed a Student’s Trajectory: Example from the Field

Ashley Paille is a 5th grade teacher at Bernon Heights Elementary School in Woonsocket, Rhode Island. She learned agency-building strategies through the Model of Instruction for Deeper Learning. Ashley shared how the model helped her students take on greater responsibility for their learning and collaborate with their peers. She highlights one student in particular who transformed as a learner as she gained higher student agency skills.

“I had a student who I taught in 4th grade and 5th grade. In 4th grade, she was very uninterested in her learning. She just was one of those students who would kind of lay back and let other people do the thinking. She was a very, very bright girl but just didn’t seem motivated to learn. Once we got into student-led team learning, when we got into the routine of having discussions, she was able to open up more. She was able to come out of her shell. She was able to make connections with the people around her.

I’ve followed through with her to 6th and 7th grade, and she’s still knocking it out of the park. She’s discussing more. She’s joined different groups at her middle school. She’s on high honors. And I really, truly believe that if she had not taken those chances to talk to people around her and learn from people around her, she might have stayed right in her shell and just let other people do the learning for her.”

Ashley Paille

Teacher, Bernon Heights Elementary School, Rhode Island

[Read more in the case study: Woonsocket Education Department Boosts Student Engagement and Achievement Through Model of Instruction for Deeper Learning]

Why Is Teacher Agency Important?

Agency in teaching consists of the capacity to make informed decisions, using professional judgement and skill (Davis, 2024). Without agency, teachers can neither develop the level of professional expertise they need to continuously improve the quality of education that their students receive, nor support the BPN and agency of their students.

Leadership Practices That Build Teacher Agency

School leaders must support the agency of teachers. As shown in Figure 3, teachers develop agency when their leaders use agency supportive practices and structures to empower teachers’ professional practice (autonomy), provide growth producing feedback (competence), and foster collaboration with peer teams (relatedness).

- Empower professional practice: The leader ensures that teachers have time and resources to learn, practice, and deepen the professional knowledge and skills they need to provide rigorous, deeper learning experiences for all students.

- Provide growth producing feedback: The leader allocates daily time to observing classroom instruction, providing feedback, and engaging with teachers about instruction. The leader also creates systems through which teachers can regularly monitor progress of their professional skills development and identify instructional practices requiring additional training or coaching support.

- Foster collaboration with peer teams: The leader provides guidelines and support for teacher teams, as well as time and resources to ensure that teacher teams become more effective over time, improving the quality of teaching and learning.

Figure 3. Principals support teacher agency through meeting teachers’ needs.

Teacher Agency in Action: Example from the Field

Justin Endicott is the principal of Huff Consolidated Elementary and Middle School in Hanover, West Virginia. He and his teachers partnered with Instructional Empowerment to implement the Model of Instruction for Deeper Learning, which included professional development and coaching support for teachers. Justin shared the impact that the partnership has had on his school as teachers developed higher agency.

“It shifted the whole culture of my building. What I’m seeing is a hum in the hallways of excitement and rich, deep learning in the content field. I see my teachers becoming deeper practitioners. They’re becoming more reflective. They’re thinking more deeply about their content and the pedagogical approaches that they’re going to take to their lessons.

Teachers say things like, ‘This is exactly what I needed.’ And it’s those comments, as a leader, that make you so happy, because you want to invest in your teachers. You want to give them the tools that they need, and you want to invest in the same way in your students. And so, to hear that feedback, as a leader, is probably the most rewarding thing from this work that I’ve had – to know that I have provided a tool for my staff, through this partnership, that allows them to be better and allows them to be more comfortable and to take risks, which will absolutely disrupt the learning environment, which is what needs to happen.

And students are more successful. The overall atmosphere that it brings is just a joyful one. We have a common language among all grade levels. We’re all working towards the same goal. We’re all working towards the same steps, and it’s just a beautiful, cohesive approach that I’ve not seen in any of the previous work that I’ve done in my career.”

Justin Endicott

Principal, Huff Consolidated Elementary and Middle School, West Virginia

Why Is School Leader Agency Important?

Instructional improvement is the leader’s primary focus. This requires the development of professionalism of leaders and teachers through continuous learning, modeling and practice to develop expertise, and reciprocity of accountability (Elmore, 2008). Professionalism arises from the principal’s strong sense of agency as a leader.

Principal Supervisor Practices That Build School Leader Agency

To develop agency in school leaders, principal supervisors must support principals’ BPN, as shown in Figure 4. Principal supervisors can support principal autonomy by distributing authority, building principal competence through coaching and professional growth opportunities, and fostering principals’ sense of relatedness by affording opportunities for principals to participate in a leadership community of practice.

- Distribute authority: The principal supervisor gives principals authority to make decisions regarding personnel, curriculum, discipline, budgets, and personnel evaluations (Chang et al., 2015).

- Provide coaching and professional growth opportunities: The principal supervisor bolsters principals’ competence through coaching conversations that convey confidence in principals’ leadership abilities and encourage the pursuit of opportunities to build leadership expertise (Chang et al., 2015).

- Provide for a leadership community of practice: The principal supervisor ensures that principals can participate in an active community of practice that deepens professional expertise while it connects principals to collegial support as they face the unique challenges of school leadership.

Figure 4. Principal supervisors can support principal agency through meeting principals’ needs.

The Impact of Principal Coaching: Example from the Field

Cassandra Wilsey is the principal of Desert Valley K-4 School in Bullhead City, Arizona. She received expert leadership coaching from Instructional Empowerment as part of a partnership around the Model of Instruction for Deeper Learning. Cassandra shared how this professional growth opportunity built her competence as an instructional leader – a hallmark of increased school leader agency.

“The coaching has really strengthened my instructional leadership because, as a principal, I’m more than just a building leader. I really set the tone and vision for what instruction should look and sound like throughout the building. Being coached on a consistent basis gives me strategies for how to communicate my vision, communicate to teachers what we’re really looking for, and it also strengthens our practice. That way, our students are getting the best education in their classrooms that we could possibly provide.

We like to joke that being a principal can be a pretty lonely job. It’s hard to find someone to really connect with and problem solve around big building level decisions. Having an instructional leadership coach has brought new perspective to things. And it’s given me a more competent voice in being an administrator for my staff and ultimately for my students in the community.”

Cassandra Wilsey

Principal, Desert Valley School, Arizona

To Sum it Up: Agency Development Is Essential for Students, Teachers, and Leaders

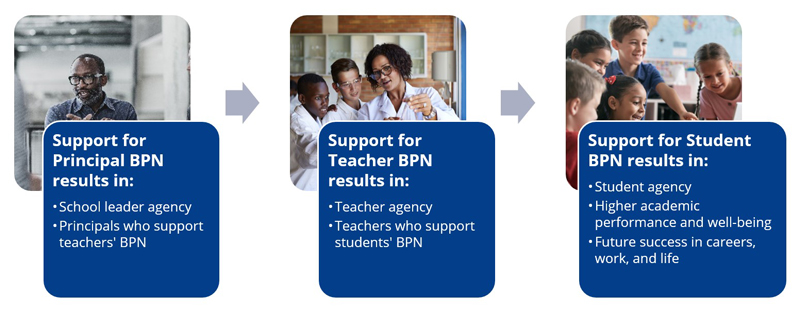

Student agency is critical to the development of knowledge and skills students need for upward mobility and success in future careers, education, and civic life. The development of agency depends upon the satisfaction of students’ basic psychological needs (BPN) for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. For teachers to support the BPN of students, teachers need agency. Teacher agency depends upon leadership support for their BPN. But for principals to support teachers’ BPN, they too must have agency. School leader agency depends upon principal supervisors’ support for principals’ BPN.

How Principal, Teacher, and Student Agency Are Interconnected

What Do You Think?

(1) If you are a principal supervisor, do your leadership practices support the agency of principals?

(2) If you are a principal, do your leadership practices support the agency of teachers?

(3) Which particular leadership practices support teacher agency? Which do not?

(4) What other factors might make school leaders more or less supportive of teacher agency?

(5) What other factors might affect the development of school leader agency?

Consider scheduling a meeting with our expert educators to discuss how you can harness teacher agency to improve student outcomes. Become the leader who creates high-quality educational experiences for ALL students.

About the Author

Dr. Merewyn Lyons

Dr. Merewyn Lyons is a Senior Research Analyst with Instructional Empowerment’s Applied Research Center. Her primary research interest is educational psychology, with a focus on understanding the effect of motivation on teaching, learning, and educational leadership. She is co-author of peer reviewed articles in Frontiers in Education, Quality Education for All, and Sage Open. Dr. Lyons is a member of the Center for Self-Determination Theory, the American Educational Research Association, and the European Association for Research on Learning and Instruction. She is also a retired officer of the United States Navy and a retired K-12 educator.

Dr. Lindsay Elliott

Dr. Lindsay Elliott is a Senior Research and Product Development Specialist at Instructional Empowerment. Dedicated to education for the past 20+ years, she has supported several Title I schools as a classroom teacher and school-based administrator. Most recently serving as principal, Dr. Elliott led turn-around efforts in a Virginian elementary school with 86% of students living in poverty and 58% English Learners, resulting in increased standardized test scores by 13% in Reading and Mathematics and 43% in Science. Lindsay is deeply committed to fostering a positive, inclusive school culture with the collective belief that ALL students have strengths and can succeed. At her core, she believes in empowering and supporting others as they strive to reach their fullest potential within a framework of high expectations, collaboration, student-centered instruction, and FUN. Dr. Elliott holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Education from Penn State University and her Master’s Degree and Doctorate from Virginia Tech in Educational Leadership and Policy Studies.

References

Ahn, I., Chiu, M. M., & Patrick, H. (2021). Connecting teacher and student motivation: Student-perceived teacher need-supportive practices and student need satisfaction. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 64(101950). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2021.101950

Bartholomew, K. J., Ntoumanis, N., Mouratidis, A., Katartzi, E., Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C., & Vlachopoulos, S. (2018). Beware of your teaching style: A school-year long investigation of controlling teaching and student motivational experiences. Learning and Instruction, 53, 50–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2017.07.006

Basileo, L. & Lyons, M.E. (2024). An exploratory analysis of Early Adopters in education innovations. Quality Education for All, 1(1), 158-179. https://doi.org/10.1108/QEA-10-2023-0009

Chang, Y., Leach, N., & Anderman, E. M. (2015). The role of perceived autonomy support in principals’ affective organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Social Psychology of Education, 18(2), 315–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-014-9289-z

Collie, R. J. (2021). COVID-19 and teachers’ somatic burden, stress, and emotional exhaustion: Examining the role of principal leadership and workplace buoyancy. AERA Open, 7, 233285842098618. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858420986187

Collie, R. J., Granziera, H., & Martin, A. J. (2019). Teachers’ motivational approach: Links with students’ basic psychological need frustration, maladaptive engagement, and academic outcomes. Teaching and Teacher Education, 86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.07.002

Davis, C. (2024). Empowering teachers: Cultivating agency in a post-pandemic educational landscape. Journal of Educational Research and Practice, 14(1), 276–285. https://doi.org/10.5590/JERAP.2024.14.1.18

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Di Domenico, S. I., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). The emerging neuroscience of intrinsic motivation: A new frontier in self-determination research. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00145

Elmore, R. F. (2008). Improving the instructional core. https://achievethecore.org/content/upload/Improving%20The%20Instructional%20Core_Elmore%20Article.pdf

Eyal, O., & Roth, G. (2011). Principals’ leadership and teachers’ motivation. Journal of Educational Administration, 49(3), 256–275. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578231111129055

Filippello, P., Larcan, R., Sorrenti, L., Buzzai, C., Orecchio, S., & Costa, S. (2017). The mediating role of maladaptive perfectionism in the association between psychological control and learned helplessness. Improving Schools, 20(2), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480216688554

Gottfried, A. E., Gottfried, A. W., Morris, P. E., & Cook, C. R. (2008). Low academic intrinsic motivation as a risk factor for adverse educational outcomes. In C. Hudley & A. E. Gottfried (Eds.), Academic motivation and the culture of school in childhood and adolescence (pp. 36–70). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195326819.003.0003

Howard, J. L., Bureau, J., Guay, F., Chong, J. X. Y., & Ryan, R. M. (2021). Student motivation and associated outcomes: A meta-analysis From self-determination theory. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(6), 1300–1323. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620966789

Jansen in de Wal, J., van den Beemt, A., Martens, R. L., & den Brok, P. J. (2020). The relationship between job demands, job resources and teachers’ professional learning: Is it explained by self-determination theory? Studies in Continuing Education, 42(1), 17–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2018.1520697

Kraft, M. A., & Lyon, M. A. (2024). The rise and fall of the teaching profession: Prestige, interest, preparation, and satisfaction over the last half century (EdWorkingPaper: 22 -679). https://doi.org/10.26300/7b1a-vk92

National Center for Education Statistics. (2023, October 17). Most public schools face challenges in hiring teacher and other personnel entering the 2023-24 academic year. https://nces.ed.gov/whatsnew/press_releases/10_17_2023.asp#:~:text=Forty%2Dfive%20percent%20of%20U.S.,year%20(2022%2D23)

National Center for Education Statistics. (2024). School pulse panel: Surveying high-priority, education-related topics. https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/spp/default.asp

Reeve, J. (2009). Why teachers adopt a controlling motivating style toward students and how they can become more autonomy supportive. Educational Psychologist, 44(3), 159–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520903028990

Reeve, J., Cheon, S. H., & Yu, T. H. (2020). An autonomy-supportive intervention to develop students’ resilience by boosting agentic engagement. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 44(4), 325–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025420911103

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Press. https://doi.org/10.1521/978.14625/28806

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

Ryan, R. M., & Niemiec, C. P. (2009). Self-determination theory in schools of education. Theory and Research in Education, 7(2), 263–272. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878509104331

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Anchor Books.

Soenens, B., Sierens, E., Vansteenkiste, M., Dochy, F., & Goossens, L. (2012). Psychologically controlling teaching: Examining outcomes, antecedents, and mediators. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(1), 108–120. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025742

Subscribe for curated education insights delivered every two weeks.

About Instructional Empowerment

Our mission is to end generational poverty and eliminate achievement gaps through redesigned rigorous Tier 1 Instruction that ensures deeper learning for ALL students.