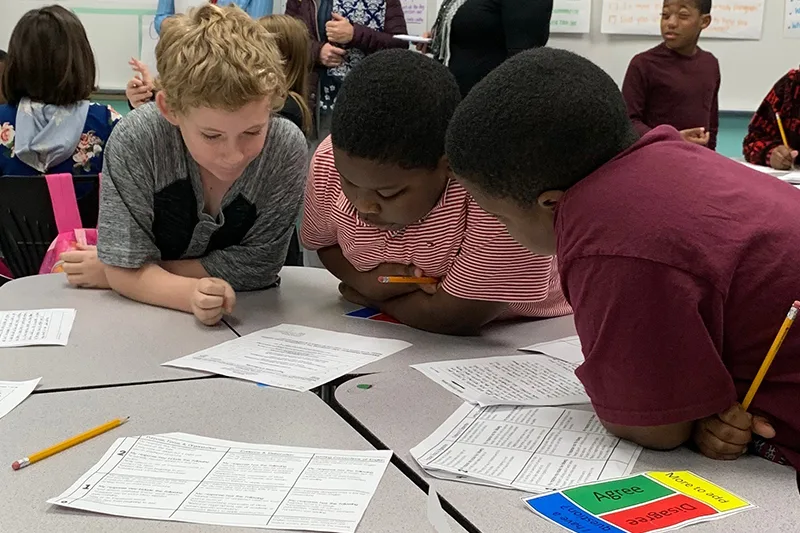

Students at William D. Moseley Elementary School became intrinsically motivated and increased their school attendance as their classrooms shifted to higher rigor and agency.

Topics Covered

- What Is Chronic Absenteeism?

- How Does Absenteeism Affect Student Outcomes?

- How Pervasive Is Absenteeism?

- What Are the Instructionally-Related Causes?

- How Effective Are Traditional Absenteeism Interventions?

- Shifting the Focus from Extrinsic to Intrinsic Motivation

- What Are the Positive Ripple Effects of Improved Attendance?

Chronic absenteeism is a growing crisis in schools across the country. Researchers warned that “our relationship with school became optional” after the pandemic (Mervosh & Paris, 2024). This mindset shift has created a need for education leaders to consider more than just traditional chronic absenteeism interventions alone.

In this article, we’ll explore the deeper root causes behind why students are chronically absent. We will focus on one powerful piece of the chronic absenteeism puzzle: making school a place where ALL students want to be because they feel challenged as valued members of a robust learning community and experience deeper learning.

What Is Chronic Absenteeism?

Most states now define chronic absenteeism as missing 10% or more school days during the year. All absences, whether excused or unexcused, are counted in this number (Henderson & Fantuzzo, 2023).

We use the term “chronic absenteeism” throughout this article since it is the most common and widely accepted term. We also recognize that others prefer “chronic absence,” which has the same definition but may emphasize that the issue is not the fault of students, a perspective with which we wholeheartedly agree.

How Does Chronic Absenteeism Affect Student Outcomes?

Research shows that students who are chronically absent often experience many negative effects associated with attendance issues, which include but are not limited to:

- Lower student achievement: Pyne and colleagues (2023) found a strong and statistically significant association between reading scores and unexcused absences, with one unexcused absence resulting in 7% of a standard deviation lower annual reading growth. Another study found that one percentage point increase in absences was associated with a .03 standard deviation decrease in academic achievement (Klein et al., 2022).

- Slower post-pandemic recovery: Districts with high post-pandemic absenteeism have experienced slower recovery, as academic performance continues to be negatively impacted (Dewey et al., 2025).

- Low academic self-concept and motivation: Absenteeism rates are significantly correlated to students’ negative beliefs in their abilities as learners and motivation to learn mathematics (Geske, et al., 2021; Vesić et al., 2021).

How Pervasive Is Chronic Absenteeism?

The number of students chronically absent from school has nearly doubled from 15% in the 2018-19 school year to 28% in the 2021-22 school year, with every state showing significant increases (The Council of Economic Advisors, 2023). In the 2022-23 school year, chronic absenteeism remained stubbornly high (Chang et al., 2025). See Figure 1. During the 2023-24 school year, the rate of chronic absenteeism dropped slightly to 23%, but remains higher than the pre-pandemic rates (FutureEd, 2025).

In the 2021-2022 school year two thirds of students attended schools with high or extreme levels of chronic absenteeism. Although chronic absence now affects students of all socioeconomic backgrounds and ethnicities, the largest increases in chronic absence occur in schools where a greater percentage of students experience poverty (Attendance Works, 2023).

Figure 1. School absences have increased from 13% before the pandemic to 23% in the latest year of data, having yet to be reduced to pre-pandemic levels.

What Are the Instructionally-Related Causes of Chronic Absenteeism?

The causes of chronic absenteeism in schools are numerous and complex, and there is no single solution. This article focuses only on the underlying causes that can be directly linked to Tier 1 instruction and which can be improved by changing the student learning experience. It does not address other very legitimate non-instructional causes including:

- Lack of access to transportation (Singer et al., 2021; Tozer & Walker, 2021)

- Family responsibilities, such as taking care of siblings (Diliberti et al., 2024; Tozer & Walker, 2021)

- Physical and mental health (Childs & Loften, 2021)

- Housing instability and homelessness (Childs & Loften, 2021; Singer et al., 2021; Tozer & Walker, 2021)

- Unsafe neighborhoods (Childs & Loften, 2021; Singer et al., 2021)

Contextual factors beyond students’ control are also associated with high rates of absenteeism, including economic disadvantage, attending schools with high percentages of students from low income households, students’ participation in special education services, and parents’ education levels (Pyne et al., 2023; Singer, 2021).

These are all important issues, but they can’t be our only focus in reducing chronic absenteeism. The most powerful and underutilized lever for change is focusing on Tier 1 instruction, which can also have a positive ripple effect on other challenges schools face. This will be detailed later in this article.

First, what does the research say about the connection between student attendance and Tier 1 instruction?

1. Students in schools with lower academic rigor have lower student attendance

A peer-reviewed study of 53 schools – with over 39% English Learners and including schools serving up to 95% of students from low socioeconomic backgrounds – found a very strong correlation between rigor in the classroom and rates of weekly student attendance. As academic rigor increased, school attendance improved.

This study used Instructional Empowerment’s Rigor Appraisal, the only known research-validated classroom walkthrough tool that measures academic rigor (Basileo, et al., 2024).

2. Students who lack a sense of belonging in school are more likely to be chronically absent

The “epidemic of absenteeism” can be attributed, in part, to social anxiety about returning to schools and a growing sense of alienation by students from their schools (New York Times Editorial Board, 2023; Jones, 2023; Vázquez Toness, 2023; Wong, 2023). Recent psychological studies indicate that more students are experiencing emotionally based school avoidance (EBSA) since the pandemic (Hamilton, 2024). Students who experience these feelings often lack a sense of belonging.

Among the most effective interventions for such students is to increase their sense of belonging by allowing students to exercise greater agency in their learning. Schools may emphasize belonging in non-academic activities (for example, pep rallies, class parties, after school sports and clubs). However, these traditional approaches lack the power of a community of scholars who learn and grow together every day in Tier 1 instruction. We will explain more in this article about why belonging is an essential component of deeper academic learning.

How Effective Are Traditional Chronic Absenteeism Interventions?

The most common attendance interventions used by districts to reduce chronic absenteeism (Diliberti et al., 2024; Conrey & Richards, 2018; Hamilton, 2024) include:

- Early warning systems to flag those students most likely to be chronically absent

- Home visits

- Calls to students’ homes

- Hiring additional staff dedicated to reducing absenteeism

- Rewards and punishments to incentivize students and their parents to improve attendance

Despite these efforts, none of these has been fully effective, and districts feel that they can have limited influence on changing the trajectory of student absences (Diliberti et al., 2024; Conrey & Richards, 2018; Lenhoff & Singer, 2022).

Educators recognize that a root cause of absenteeism is boredom: “To ask kids to sit in rows and columns and listen to somebody lecture at them for seven hours a day is just not something they’re going to put up with anymore” (Diliberti et al., 2024, p. 8). Nevertheless, traditional chronic absenteeism interventions often put little to no focus on improving students’ experience of classroom instruction.

Subscribe for curated education insights delivered every two weeks.

Shifting the Focus of Tier 1 Instruction from Extrinsic to Intrinsic Motivation

Even before the pandemic, Gallup’s surveys of students from every state found that 53% of students were not engaged in school or were actively disengaged – simply going through the motions at best, or actively disrupting teaching and learning at worst (Hodges, 2018). When students don’t feel engaged and motivated, school absenteeism can worsen.

We have identified two major underlying issues in Tier 1 instruction that affect student motivation and often go unnoticed and unaddressed:

- Teacher-directed instruction: The traditional 19thcentury model of instruction where students sit passively and listen to teachers for extended periods is the most prevalent model in schools today, but it is no longer interesting for 21st century learners.

- The effects of screen time on students: The students of today are undeniably more difficult to engage. Students’ attention spans, self-control, empathy, and other skills have been eroded by excessive screen time (Qu et al., 2023).

Extrinsic rewards and consequences will not reverse the maldevelopment effects of excessive screen time. Efforts to engage students in quick but shallow ways like themed spirit days will not genuinely motivate students when their role in learning remains one of passive compliance. So, what will motivate students to attend school?

Humans are wired to engage when they find something inherently interesting. Memorization and worksheets are not inherently interesting. Some students will comply and complete their assignments to get the grade, but grades are extrinsic motivation.

Even more concerning is that other students will disconnect from their learning altogether and become amotivated. Recall the Gallup poll mentioned above – 53% of students are not engaged or actively disengaged – this means the majority of our students fall into the amotivation category (see Figure 2). Amotivation explains, in part, the chronic absenteeism epidemic – especially in the cases where the barrier to student attendance is students’ feelings of alienation and anxiety associated with school.

The goal must be to create a learning environment of intrinsic motivation where all students want to learn and want to come to school.

Figure 2. Instructional Empowerment’s research-based continuum of student motivation shows examples of how students feel when they are experiencing amotivation, extrinsic motivation, and intrinsic motivation in school.

Increasing Intrinsic Motivation by Developing Student Agency

Creating a learning environment of intrinsic motivation means that Tier 1 instruction must develop students’ agency. We define student agency as the ability of students to self-direct their own learning, which involves:

- Establishing worthy goals

- Organizing actions toward their goals

- Self-reflecting on progress

- Developing persistence

Students with agency become their own agents of change for self-improvement and advancement. These are the skills all students need to be successful in school and in life. The development of agency also mitigates the maldevelopment effects of excessive screen time.

What conditions need to be in place in Tier 1 instruction for students to develop agency? Our Applied Research Center has studied this very question, analyzing the science behind how human motivations affects student learning and skill development.

We have grounded our work with schools and districts in self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017). This theory states that all human beings have three basic psychological needs:

(1) Autonomy: Choice and ownership

(2) Competence: Confidence in one’s own abilities

(3) Relatedness: Sense of belonging

If these three needs are met, students develop agency, become intrinsically motivated in their learning, and want to attend school.

But if even one of these needs is not met, students can become amotivated. For example:

(1) Autonomy thwarted: Students experience prescribed interventions where they have little voice and choice, especially students who are struggling academically or behaviorally.

(2) Competence thwarted: Students don’t feel smart or academically capable.

(3) Relatedness thwarted: Students aren’t connecting with peers and don’t feel acceptance.

What we have found is that the model of instruction in classrooms must be intentionally selected to meet these three needs and develop student agency. Most school districts have not made a conscious choice about their model of instruction and are operating within the “default” teacher-directed model that is not conducive to student agency. Realizing this empowers education leaders to take action on the root cause of low intrinsic motivation and student disengagement and address a significant contributor to the problem of chronic absenteeism.

A Model of Instruction Designed to Develop Student Agency

The evidence-based Model of Instruction for Deeper Learning was designed by Instructional Empowerment’s Applied Research Center to intentionally develop student agency and meet students’ innate motivational needs.

How the Model Builds Autonomy in Tier 1 Instruction

When students have voice and choice in an autonomy-supportive environment, they feel they’re part of their learning. In contrast, if the teacher owns everything and directs students – which is what happens in the traditional teacher-directed model of instruction – most students won’t take ownership. Those who do take ownership of their learning are typically motivated by grades. Students who are experiencing amotivation won’t be motivated by extrinsic means like grades because they’ve already checked out. Consequences will only alienate them further.

In the team structures of the Model of Instruction for Deeper Learning, students experience intrinsic motivation as they are given real roles and responsibilities within a team structure so they can build ownership over their own learning. They learn to use their team protocols and resources to problem solve with their peers, requiring less support from the teacher.

How the Model Fosters Competence in Tier 1 Instruction

Once students begin leading their own learning with a rigorous task that requires them to think, discuss, activate their peers as learning resources, and share background knowledge, it’s inherently more interesting and motivating to them than traditional teacher-directed instruction.

Each team member becomes a trusted peer and problem solver, allowing the team to successfully tackle much more rigorous learning tasks than the teacher may have been comfortable providing when students were doing individualized or traditional group work. The Model of Instruction for Deeper Learning opens access to more rigorous content for all students. Teams persist through productive struggle together and lift each other up as their academic confidence flourishes.

How the Model Creates Relatedness in Tier 1 Instruction

Students who engage in student-led team learning often talk about how they become friends with their classmates. They may not have had many friends before, as they sat silently listening during teacher-directed instruction. Friend groups are very powerful for motivating students to want to attend school.

When students are absent, they miss the camaraderie of their learning teams. Having a role and responsibility and respect and empathy among peers helps them see why attendance is important – because their team needs them. They begin to feel connected and safe with their team, and they are more willing to be vulnerable as learners, which is incredibly powerful and reduces the social anxiety that may have been causing student absenteeism.

The Model of Instruction for Deeper Learning has structures for students to bring their unique background knowledge and voices to their teams and participate equally. They can be their authentic selves and feel a sense of belonging as they encourage, support, and challenge one another in academic tasks.

A Reason to Come to School

A classroom environment of high rigor and high agency with student-led team learning makes students feel they are an indispensable part of a learning community. They become interested in their learning, they don’t want to let their team members down, and their motivation to attend school increases. That is the real power of the model – it gives students a reason to come to school.

High School Students Improve Attendance and Engagement: Example from the Field

Katie Endicott is the principal of Westside High School in Hanover, West Virginia. She and her school partnered with Instructional Empowerment to implement the Model of Instruction for Deeper Learning. Katie shared the positive changes she sees as students experience the model, realize that their presence in the classroom matters, and improve their school attendance.

“We are seeing student autonomy and ownership take place. I believe that’s been one of the most beneficial and powerful shifts that I’ve seen. Students now care about being in the classroom. They care about their learning. They understand that they are in a team, and in this room they are a facilitator, a team member, or a record keeper. They know that they have different roles in their teams and that every role is powerful. Every role is beneficial, and they feel like it matters. Their presence in the classroom matters because now they’re not just doing a worksheet that they can make up after they’ve missed three days. They’re actually part of a team, and they’re working together on a task.”

Katie Endicott

Principal, Westside High School, West Virginia

What Are the Positive Ripple Effects When Students Improve Their Attendance?

Schools and districts who have shifted to a student-led model of instruction realize many positive effects. In addition to improved student attendance, the impacts also include:

As students go home excited to talk about their school day, their parents begin to see positive changes in their children as well. Parents talk to other parents, and enrollment growth starts to take off because the school and district changed the student learning experience.

Elementary School Sees Increased Community Pride and Enrollment Growth

Cornethia Foreman is the parent of a fifth-grader at William D. Moseley Elementary School. The school partnered to implement student-led team learning. Cornethia highlighted how the community began to buzz about Moseley as it shifted from a school that had received the lowest accountability rating from the state to one in which other parents were eager to enroll their children.

“I think Moseley is the best school we have in Putnam County – the staff supports every student to excel. We knew it would take more than a year. In the second year we started blooming. Parents were on Facebook bragging about Moseley. People are trying to get their kids into Moseley now. They have to drive— sometimes far out of their way—to get their kids here. Even upscale people who can be picky want their kids here. It wasn’t like that at first, but they see the change in Moseley. My son has learned so much from being here. I hate that he has to move on, now that he’s graduating to middle school. All my grandkids will go to Moseley. I’m definitely proud to be a Moseley parent”

Cornethia Foreman

Parent to a fifth grader, William D. Moseley Elementary School, Putnam County, Florida

[Read more in the case study: Becoming a School Where All Students Thrive]

Lead the “Chronic Absenteeism Intervention” That Will Make School Worth Attending

Armed with the knowledge of the deeper root causes behind chronic absenteeism and what motivates student learning, you have the power to ensure school is a place that all students want to be. It isn’t another attendance intervention after all – it is a shift in your model of instruction and the learning experience of all students.

Consider scheduling a meeting with our expert educators to discuss best practices for how Tier 1 instruction can address the unique challenges of chronic absenteeism in your school or district.

About the Author

Michael D. Toth

Michael D. Toth is founder and CEO of Instructional Empowerment (IE) and leads IE’s Applied Research Center. He is also the author of the multi-award-winning book The Power of Student Teams with David Sousa; author of Who Moved My Standards; and co-author with Robert Marzano of multiple books. Most recently, he co-authored peer-reviewed research articles published in academic journals in collaboration with researchers Lindsey Devers Basileo, Merewyn Lyons, Barbara Otto, and Natalie Vannini.

Michael is a keynote speaker at conferences and coaches and mentors superintendents on creating a bold instructional vision, designing and launching a high-functioning cabinet team, transforming Tier 1 core instruction, and leading systems-based school advancement.

Learn more about Michael: https://instructionalempowerment.com/ie-founder-michael-d-toth/

Dr. Merewyn Lyons

Dr. Merewyn Lyons is a Senior Research Analyst with Instructional Empowerment’s Applied Research Center. Her primary research interest is educational psychology, with a focus on understanding the effect of motivation on teaching, learning, and educational leadership. She is co-author of peer reviewed articles in Frontiers in Education, Quality Education for All, and Sage Open. Dr. Lyons is a member of the Center for Self-Determination Theory, the American Educational Research Association, and the European Association for Research on Learning and Instruction. She is also a retired officer of the United States Navy and a retired K-12 educator.

References

Attendance Works. (2023, November 17). All hands on deck: Today’s chronic absence requires a comprehensive district response and strategy. https://www.attendanceworks.org/todays-chronic-absenteeism-requires-a-comprehensive-district-response-and-strategy/

Basileo, L. D., Lyons, M. E., & Toth, M. D. (2024). Leading indicators of academic achievement: Investigating the predictive validity of an observation instrument in a large district. Sage Open, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440241261119

Chang, H., Balfanz, R.M. Byrnes, V. (2025). Continued high levels of chronic absence, with some improvements, require action. Attendance Works. https://www.attendanceworks.org/continued-high-levels-of-chronic-absence-with-some-improvements-require-action/

Childs, J., & Lofton, R. (2021). Masking attendance: How education policy distracts from the wicked problem(s) of chronic absenteeism. Educational Policy, 35(2), 213-234. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0895904820986771#tab-contributors

Conry, J. M., & Richards, M. P. (2018). The severity of state truancy policies and chronic absenteeism. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 23(1-2), 187-203. https://doi.org/10.1080/10824669.2018.1439752

Council of Economic Advisors. (2023, September 13). Chronic absenteeism and disrupted learning require an all-hands-on-deck approach. https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/cea/written-materials/2023/09/13/chronic-absenteeism-and-disrupted-learning-require-an-all-hands-on-deck-approach/

Dewey, D.C., Fahle, E., Kane, T.J. Reardon, S.F., Staiger, D.O. (2025). Pivoting from pandemic recovery to long-term reform: a district-level analysis. Education Recovery Scorecard. https://educationrecoveryscorecard.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Pivoting-from-Pandemic-Recovery-to-Long-Term-Reform-A-District-Level-Analysis.pdf

Diliberti, M. K., Rainey, L. R., Chu, L., Schwartz, H. L. (2024). Districts try with limited success to reduce chronic absenteeism. RAND. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA956-26.html

FutureEd. (2025, February 7). Tracking state trends in absenteeism. https://www.future-ed.org/tracking-state-trends-in-chronic-absenteeism/

Geske, A., Kampmane, K., Ozola, A. (2021). The influence of school factors on students’ self-concept: Findings from PIRLS 2016. Human, Technologies and Quality in Education. https://doi.org/10.22364/htqe.2021

Hamilton, L. G. (2024). Emotionally based school avoidance in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic: Neurodiversity, agency and belonging in school. Education Sciences, 14, 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14020156

Henderson, C. M., & Fantuzzo, J. W. (2023). Challenging the core assumption of chronic absenteeism: Are excused and unexcused absences equally useful in determining academic risk status? Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 28(3), 259-293. https://doi.org/10.1080/10824669.2022.2065636

Hodges, T. (2018). School Engagement Is More Than Just Talk. Gallup. https://www.gallup.com/education/244022/school-engagement-talk.aspx

Klein, M., Sosu, E. M., & Dare, S. (2022). School absenteeism and academic achievement: Does reason for absence matter? AERA Open, 8(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1177/23328584211071115

Lenhoff, S. W., & Singer, J. (2022). Promoting ecological approaches to educational issues; Evidence from a partnership around chronic absenteeism in Detroit. Peabody Journal of Education, 97(1), 87-97. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2022.2026723

Mervosh, S. & Paris, F. (2024). Why school absences have “exploded” almost everywhere. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2024/03/29/us/chronic-absences.html

Singer, J., Pogodzinski, B., Lenhoff, S. W., & Cook, W. (2021). Advancing an ecological approach to chronic absenteeism: Evidence from Detroit. Teachers College Record, 123(4), 1-36. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146812112300406

Tozer, S., & Walker, L. (2021). Reducing chronic absence: Making equity strategies specific, adaptive, and evidence-based. University of Illinois Chicago Center for Urban Education Leadership. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED622177.pdf

Pyne, J., Grodsky, E., Vaade, E., McCready, B., Camburn, E., & Bradley, D. (2023). The signaling power of unexcused absence from school. Educational Policy, 37(3), 676-704. https://doi.org/10.1177/08959048211049428

Qu, G., Hu, W., Meng, J., Wang, X., Su, W., Liu, H., Ma, S., Sun, C., Huang, C., Lowe, S., & Sun, Y. (2023). Association between screen time and developmental and behavioral problems among children in the United States; Evidence from 2018 to 2020 NSCH. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 161, 140-149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.03.014

Vesić, D., Džinović, V., & Mirkov, S. (2021). The role of absenteeism in the prediction of math achievement on the basis of self-concept and motivation: TIMMS 2015 in Serbia. Psihologija, 54(1), 15-31. https://doi.org/10.2298/PSI190425010V

Subscribe for curated education insights delivered every two weeks.

About Instructional Empowerment

Our mission is to end generational poverty and eliminate achievement gaps through redesigned rigorous Tier 1 Instruction that ensures deeper learning for ALL students.