Pictured above: Through student-led behavior management strategies, Lakewood Elementary School experienced a surge in positive behaviors as students engaged in team learning.

Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) has been helpful for many schools and districts to establish foundational structures that improve conditions for students and teachers.

However, if schools remain at the foundational level with teacher-directed systems of control, it can negatively impact school culture and even exacerbate challenging student behavior. This article explores how schools and districts can go further, improving student behavior and achievement through the student-led behavior management strategies of the Model of Instruction for Deeper Learning.

Going Beyond PBIS

PBIS establishes foundations for improving school and classroom conditions by helping students understand rules and expectations. PBIS can provide students and teachers with basic structures and consistency, ensure that students know the consequences of their actions, and help establish positive teacher-student relationships.

However, after laying these foundations, an overemphasis on control can create a restrictive environment that perpetuates behavior issues rather than resolving them. When control becomes the focus, students often disengage from their learning. Research shows that controlling teaching practices are associated with student oppositional defiance and student amotivation (Flamant et al., 2023).

The Typical Student Experience in an Environment of Overcontrol

Students have few options to exercise voice and choice in an environment of overcontrol. This limited sense of agency – where students lack meaningful opportunities to self-direct their actions – is often a root cause of challenging student behavior.

Common occurrences when students feel overcontrolled:

- Students feel they are only able to exercise two choices: comply or resist.

- Some students comply, passively following the teacher’s directions. These students often need external rewards to continue in compliance.

- Other students may passively resist by laying their heads down and disengaging from instruction.

- Students with high energy levels may actively resist through behaviors that the teacher finds disruptive.

- Students may be removed from the classroom for disruptions and sent to behavioral interventions, the principal’s office, or asked to sit in the hallway.

- Sometimes students may be isolated to the back of the classroom and lose any privileges of interacting with peers.

In all of these situations, students are either fully or partially losing their access to learning.

Students who are removed from Tier 1 instruction for behavior can suffer academic impacts:

- Exclusionary discipline is associated with worse academic outcomes, such as low test scores and grade retention (Anderson et al., 2019).

- Across student groups, single out-of-school suspensions have a negative effect on reading and/or mathematics proficiency over time (Yaluma et al., 2021).

Even students who remain passively compliant are missing out on the opportunity to engage as an active participant and learn more deeply.

The Connection Between Behavior and Academic Achievement

An important consideration with PBIS is that it may fall short of the ultimate goal of education: deeply engaging students in their academics.

- PBIS Has Mixed Impact on Academic Achievement: To bolster efforts to improve student academic performance, many schools and districts include schoolwide positive behavioral interventions and supports (PBIS) and other forms of multi-tiered preventive behavioral programs. Although these programs have demonstrated effectiveness in fostering prosocial conduct in students, evidence of its impact on academic achievement is mixed (Gage et al., 2015; Gage et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2018).

- When Schools Focus on Improving Academic Rigor, Behavior Follows: Our Applied Research Center found that as schools increased their scores on a tool that measures academic rigor, student behavior referrals and suspensions decreased (Basileo, et al., 2024).

Simply increasing academic rigor within a traditional teacher-directed model of instruction will often leave many students behind. What allows all students to access rigor and engage authentically in deeper learning is shifting to a student-led model of instruction.

Authentic Engagement Through a Student-Led Model of Instruction

Students productively engaged with their teams at Wiliam D. Moseley Elementary School.

Traditional behavior systems often rely on extrinsic motivation – rewards for good behavior or consequences for disruptions. While effective in the short term, these approaches don’t engage students authentically in the learning process or develop intrinsic motivation.

Shifting from a teacher-directed to student-led learning environment helps students develop a sense of purpose and belonging, leading to intrinsic motivation and naturally improved behavior.

- The Teacher’s Role: Teachers move from directing and controlling behavior to coaching students to take on leadership roles within learning teams.

- Students’ Roles: Students take ownership of their team roles, responsibilities, and norms, transforming behavior management from a system of compliance to a system of shared accountability. Students become authentically engaged and willingly invest their discretionary effort into their learning – because they want to not because they have to.

What Students Experience in Student-Led Teams

Through student-led team learning, students bring their individual identities, background knowledge, and cultural experiences into rich academic discourse with their peers. As teams form a sense of belonging, students feel intrinsically motivated to learn and develop empathy for one another. They want to do their best because their team members rely on them to fulfill their roles and responsibilities.

In our partner schools, students who used to receive discipline referrals for behavior often become role models in the classroom. They find pride in their work and have an outlet for their energy, intelligence, and skills. Sitting passively in compliance was never engaging for these students, but a meaningful role in learning inspires them to live up to high expectations – all because the model of instruction in the classroom moved from teacher-directed to student-led through the Model of Instruction for Deeper Learning.

“One of my students wanted to be the class clown in the back of the room and not really participate or engage in the learning. Through student-led team learning techniques, he became fully engaged with 100% ownership by the middle of the school year. He actually asked me if he could be the team facilitator. He fully committed to that role. He went from being the one who was struggling to being the leader who helps those who are struggling.”

Shanna Cribbs

Teacher, William D. Moseley Elementary School

Subscribe for curated education insights delivered every two weeks.

Redefining Positive Student Behavior

What is positive student behavior? Traditionally, positive student behaviors might be defined as:

- Sitting quietly without causing disruptions

- Listening to the teacher

- Waiting to be called upon

- Refraining from interacting with classmates during instruction

This behavior aligns with the 19th century model of teacher-directed instruction that still dominates most classrooms today. While brief periods of this behavior are necessary, traditional teacher-directed instruction is not ideal for developing more advanced positive student behaviors. We are redefining positive behavior from self-regulation for compliance to self-regulation and peer regulation for the purposes of students leading their own learning.

“The factory model assumed that the best way to educate students was to standardize instruction, putting learners in large groups, and moving them along their identified conveyor belt to passively receive the information transmitted to them by the teacher. We now know that every student is on a distinctive developmental trajectory and that agency and engagement support deeper learning, which leads to learning ability.

This means that schools must evolve from methods that place individual students at individual desks to memorize information and fill in worksheets to environments designed for active and collaborative inquiry, the fundamental way that human beings learn.”

Linda Darling-Hammond (2024, p. 220)

What Does Positive Behavior Look Like in the Model of Instruction for Deeper Learning?

The Model of Instruction for Deeper Learning TM provides teachers and students with the structures, resources, and support to redefine positive student behavior as students become leaders of their own learning.

Positive student behavior takes on a whole new meaning as students acquire skills for deeper learning, progressing from novice to expert. They gradually develop a greater understanding of the purpose behind the skills they are learning and how the skills interconnect and support learning (National Research Council, 2000, 2012. National Academics of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018).

For example, within the Model of Instruction for Deeper Learning, students learn how to:

- Communicate respectfully

- Help others solve problems

- Recognize and admit errors

- Resolve conflicts and disagreements

- Demonstrate empathy and perspective-taking

- Motivate and mentor peers

- Address disruptive behaviors within their teams

- Plan and set team goals

- Co-create the learning culture

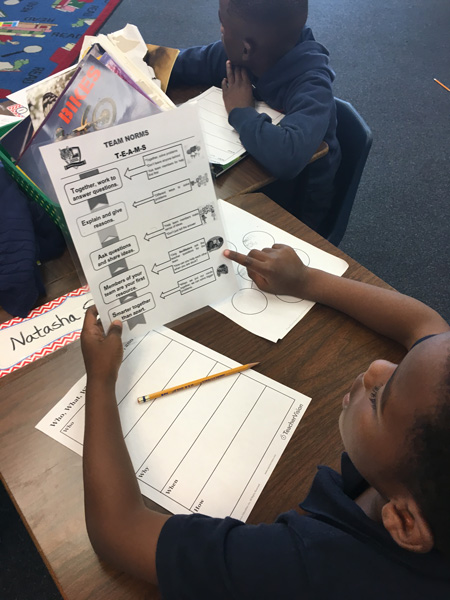

A Lakewood Elementary School student reviews a protocol from the Model of Instruction for Deeper Learning. Lakewood redefined positive student behavior, students developed advanced skills, and schoolwide conditions improved as a result.

As the Model of Instruction for Deeper Learning develops high levels of positive behavior, students not only engage more deeply, but achievement gaps also narrow.

We are redefining positive behavior from self-regulation for compliance to self-regulation and peer regulation for the purposes of students leading their own learning.

Student-Led Behavior Management

Classrooms that implement student-led behavior management – rather than relying on traditional teacher-led control – see significant improvements in student engagement, positive behavior, and motivation. Through the Model of Instruction for Deeper Learning, students learn strategies to self-regulate their behavior as part of a collaborative learning team.

Key Strategies for Student-Led Behavior Management

(1) Roles and Responsibilities: Students are trained to take on specific roles within their teams and learn how to use protocols to participate equally in academic discourse. Students rotate roles so all students get the opportunity to have a leadership role. Team protocols ensure equality of voice and participation within the teams.

(2) Rigorous, Collaborative Tasks: Instead of passively listening, students are given challenging tasks where they can activate their background knowledge, share different perspectives, and learn from their peers. All students gain access to more challenging curriculum content through supportive team structures and resources.

(3) Teacher as Coach, Not Director: Teachers learn how to move from lengthy lectures and low rigor independent practice to focused mini lessons that set the stage for rigorous, student-led team tasks. Teachers monitor and coach students to ensure they are performing their roles and responsibilities and reaching their learning targets, preventing any daily learning gaps from forming.

(4) Autonomy Supportive Learning Environment: Students are granted more voice and choice where they have input on how to approach learning tasks within their teams. Through the model, they gain a toolbox of strategies for how to work together effectively. This sense of autonomy and responsibility leads to greater intrinsic motivation.

(5) Team Culture and Peer Accountability: As students become more comfortable in their roles, they begin to challenge one another to meet team norms and ensure that positive behavior is maintained. The classroom culture transitions from teacher-controlled behavior management to student-led agency. Student teams mature into a student-led learning community of scholars, engaging in rich academic discourse.

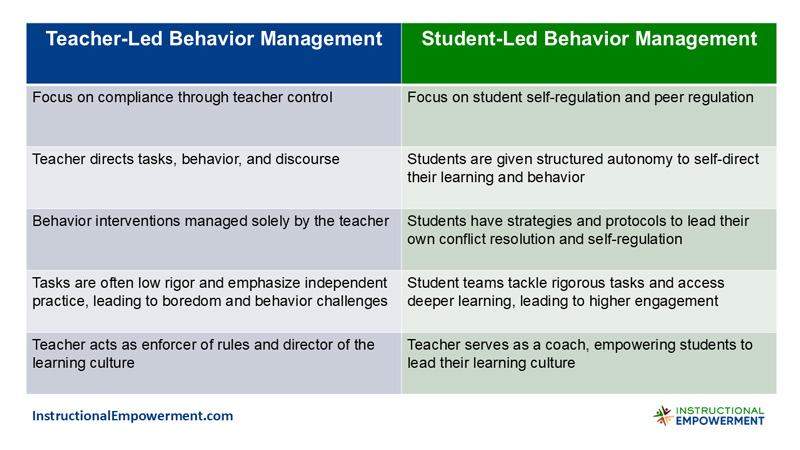

Contrasting Teacher-Led vs. Student-Led Behavior Management

Teachers consistently report that the Model of Instruction for Deeper Learning quickly transforms student behavior, even for students previously labeled as disruptive. Once students have a meaningful role and leadership responsibilities in their learning process, behavioral challenges dissipate and intrinsic motivation flourishes.

“Before, students with learning disabilities or major learning gaps expressed themselves through anger because they didn’t know what else to do…Now, the barriers are gone for those students. Everybody has a role in their teams. Everybody has a job and everybody is important.”

Shelby Bellamy

Teacher, William D. Moseley Elementary School

About the Author

Michael D. Toth

Michael D. Toth is founder and CEO of Instructional Empowerment (IE) and leads IE’s Applied Research Center. He is also the author of the multi-award-winning book The Power of Student Teams with David Sousa; author of Who Moved My Standards; and co-author with Robert Marzano of multiple books. Most recently, he co-authored peer-reviewed research articles published in academic journals in collaboration with researchers Dr. Basileo, Dr. Lyons, Dr. Otto, and Dr. Vannini.

Michael is a keynote speaker at conferences and coaches and mentors superintendents on creating a bold instructional vision, designing and launching a high-functioning cabinet team, transforming Tier 1 core instruction, and leading systems-based school advancement.

Learn more about Michael: https://instructionalempowerment.com/ie-founder-michael-d-toth/

References

Anderson, K. P., Ritter, G. W. & Zamarro, G. (2019). Understanding a vicious cycle: The relationship between student discipline and student academic outcomes. Educational Researcher, 48(5), 251-262. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X19848720

Basileo, L. D., Lyons, M. E., & Toth, M. D. (2024). Leading indicators of academic achievement: Investigating the predictive validity of an observation instrument in a large district. Sage Open, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440241261119

Darling-Hammond, L. (2024). Reinventing systems for equity. ECNU Review of Education, 7(2), 214-229. https://doi.org/10.1177/20965311241237238

Flamant, N., Haerens, L., Loeys, T., Vermote, B., & Soenens, B. (2023). ‘Help, my teacher is pressuring me!’ The role of students’ coping with controlling teaching in motivation and engagement. Motivation and Emotion 47, 739–760. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-023-10018-1

Gage, N. A., Sugai, G., Lewis, T. J., & Brzozowy, S. (2015). Academic achievement and schoolwide positive behavior supports. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 25(4), 199-209. https://doi.org/10.1177/1044207313505647

Gage, N. A., Leite, W., Childs, K., & Kincaid, D. (2017). Average treatment effect of school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports on school-level academic achievement in Florida. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 19(3), 158-167. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300717693556

Kim, J., McIntosh, K., Mercer, S. H., Nese, R. N. T. (2018). Longitudinal associations between SWPBIS fidelity of implementation and behavior and academic outcomes. Behavioral Disorders, 43(3), 357-369. https://doi.org/10.1177/0198742917747589

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2018). How People Learn II: Learners, Contexts, and Cultures. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/24783

National Research Council (2000). How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/9853

National Research Council (2012). Education for Life and Work: Developing Transferable Knowledge and Skills in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13398

Yaluma, C. B., Little, A. P., & Leonard, M. B. (2021). Estimating the impact of expulsions, suspensions, and arrests on average school proficiency rates in Ohio using fixed effects. Educational Policy, 35(7), 1731-1758. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904821999838

Subscribe for curated education insights delivered every two weeks.

About Instructional Empowerment

Our mission is to end generational poverty and eliminate achievement gaps through redesigned rigorous Tier 1 Instruction that ensures deeper learning for ALL students.