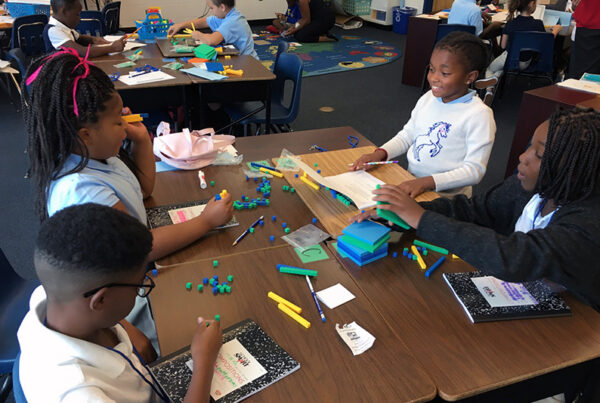

Students at a partner school in Des Moines engage in student-led team learning.

By: Michael D. Toth

Despite efforts to recover from the pandemic’s impact, academic performance in many school districts remains lower – and more unequal – except in the wealthiest communities in America (Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University, 2024).

Improving student achievement and closing achievement gaps is complex and involves looking beyond the visible symptoms. This article will examine five invisible root causes that affect students’ academic performance and will offer insights for addressing them.

What Is the Daily Learning Gap?

The achievement gap is the result of a culmination of small daily learning gaps for students in Tier 1 instruction. If left unaddressed, daily learning gaps manifest as an achievement gap over time and require Tier 2 and 3 interventions.

Educators have much more influence to impact the daily learning gap for all students than they often believe they do. Focusing on closing the daily learning gap is manageable – and very powerful. Eliminating the daily learning gap can mitigate the effects of opportunity gaps over time and keep achievement gaps from ever forming. This is possible through redesigned Tier 1 instruction, which will be covered in more detail below.

The achievement gap is the result of a culmination of small daily learning gaps. Educators have much more influence to impact the daily learning gap for all students than they often believe they do.

What Are the Typical Approaches to Closing Achievement Gaps?

First, let’s examine how traditional strategies attempt to address learning gaps – and why those strategies have not yielded the level of results needed for many students.

- Tutoring programs: While some forms of tutoring may benefit students, and many districts invest significant funding into expanding tutoring programs to try to reach more students, the expectation that tutoring alone will be enough to close achievement gaps is unrealistic.

- For example, a large research study of almost 7,000 students found that tutoring led to only a small increase in reading scores and no increase in math scores over a period of two years (Kraft, Edwards, & Cannata, 2024).

- Another study found that the effects of tutoring programs decline as they scale in size (Kraft, Schueler, & Falken, 2024).

- Interventions: Although many studies of interventions to build students’ academic skills reveal moderate to strong effect sizes, meta-analyses of follow-up studies indicate fading effects, sometimes within months, of completion (Bailey et al., 2020).

- An example of what “fading effects” might look like in practice is if a student was referred to interventions to develop skills in recognizing letter-sound relationships so that they can correctly decode words. They develop that skill then leave the intervention. But the student does not experience rigorous and supportive Tier 1 instruction that helps them develop comprehension skills of the words that they can now decode. This student still cannot understand what they have read even though they “successfully” completed the intervention. Without reinforcement of the decoding by taking it to the next level, that skill fades.

- PBIS and behavioral supports: To bolster efforts to improve student academic performance, many schools and districts include schoolwide positive behavioral interventions and supports (PBIS) and other forms of multi-tiered preventive behavioral programs. Although these programs have demonstrated effectiveness in fostering prosocial conduct in students, evidence of its impact on academic achievement is mixed (Gage et al., 2013; Gage et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2018).

One very important factor remains unchanged in each of the traditional approaches above – an emphasis on attempts to close achievement gaps after they have formed instead of redesigning Tier 1 instruction so gaps are less likely to form in the first place.

How Can Redesigned Tier 1 Instruction Close Opportunity Gaps and Achievement Gaps?

While typical approaches to closing achievement gaps, like the ones described above, tend to focus on symptoms, redesigned Tier 1 instruction addresses the invisible root causes that create the daily learning gap and compound into achievement gaps over time.

5 Root Causes of Low Achievement and Achievement Gaps

When low achievement and learning gaps persist for years despite efforts to improve schools, it is because the invisible root causes have not yet been fully addressed. The following five root causes are often the most pervasive in school districts around the country:

- Low rigor Tier 1 instruction

- Low engagement Tier 1 instruction

- A focus on surface learning vs. deeper learning

- Teacher-directed instruction vs. student-led team learning

- Overreliance on Tier 2 and 3 interventions

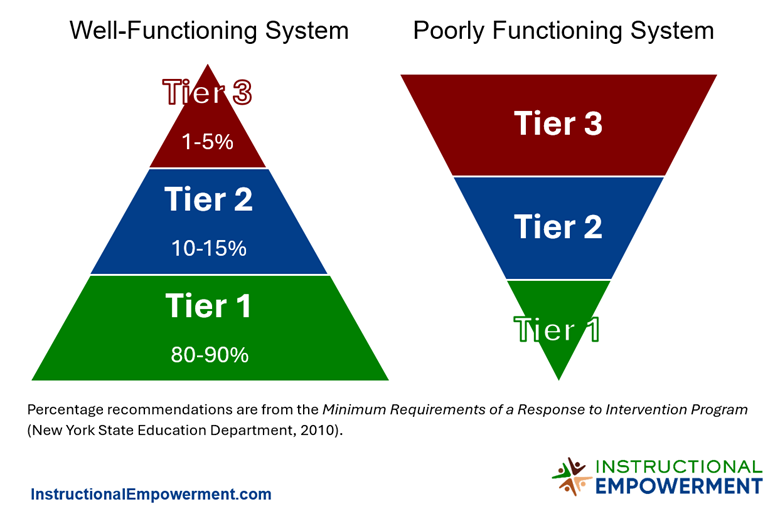

Root Cause 1: Low Rigor Tier 1 Instruction

How Does Low Rigor Tier 1 Instruction Affect Academic Achievement?

In a learning environment of low rigor in Tier 1 instruction, daily learning gaps turn into achievement gaps as the following occur:

- Students are not exposed to rigorous grade level content and/or do not have the supports needed to master it.

- Students are not using content vocabulary in academic discourse with peers.

- Students do not have opportunities in the classroom to increase their background knowledge and connect it to new learning to make sense of complex concepts.

It is incredibly difficult to increase every student’s access to rigorous learning with the student-to-teacher ratios we have in classrooms today and the different needs of each student. The key is to create a student-led team learning environment where structures, protocols, and roles create self-managing, self-directed learning teams (Toth & Sousa, 2019).

Closing Gaps and Increasing Student Achievement with High Rigor Tier 1 Instruction

In a student-led team learning environment, students learn to support each other and persist through productive struggle. Teachers who engage in the Model of Instruction for Deeper Learning learn to become coaches to their students, increasing the rigor of the teams’ tasks as students rise to meet the challenge and increase their capacity for more rigor.

The positive effects of increasing the rigor of Tier 1 instruction include:

- Increased cognitive engagement as students must help one another unpack and understand rigorous content.

- Elevated academic discourse as students verbalize content vocabulary with peers and share background knowledge.

- Improved self-efficacy as students see themselves begin to succeed academically and improve their ability to access rigorous learning.

Root Cause 2: Low Engagement Tier 1 Instruction

How Does Low Engagement Tier 1 Instruction Affect Academic Achievement?

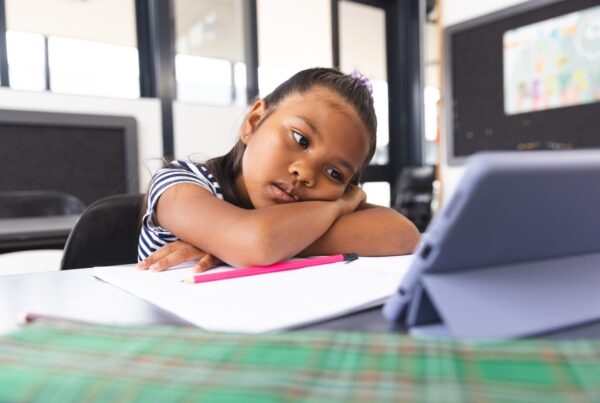

The correlation between high student engagement and improved academic outcomes has a strong research history (Dyer, 2015). Yet, even before the pandemic, 53% of students said they were not engaged or were actively disengaged in school (Hodges, 2018).

The students of today are much more difficult to engage in the classroom. According to a 2020 study of screen time among children in the United States (Qu et al., 2023), the average amount of time students spend interacting with technology far exceeds the recommendations of the World Health Organization, and excessive screen time in children and adolescents is associated with:

- Poorer attention skills

- Lower cognitive skills

- Negative impact on working memory

- Lower empathy

- Less self-control

- Decrease in social coping skills and emotional regulation

What this means is that today’s students have a reduced ability to sit passively and listen to their teachers for an extended period of time. They are just not wired for this type of low engagement Tier 1 instruction – but shifting to a high engagement learning environment can make a huge difference.

Closing Gaps and Increasing Student Achievement with High Engagement Tier 1 Instruction

Although a tempting solution is to add more screen time in education in an attempt to make the classroom more engaging, we cannot mitigate the harmful maldevelopment effects of excessive screen time with even more screen time. We must redesign Tier 1 instruction to engage students more deeply in their learning and prevent daily learning gaps and achievement gaps.

What does high engagement Tier 1 instruction look like?

- Human-to-human interaction as students collaborate with peers, building up the interpersonal skills that excessive screen time has eroded.

- Rigorous and powerful peer discourse around challenging tasks that develop students’ persistence and ability to concentrate for longer periods of time.

- Agency and accountability as students develop the intrinsic motivation to take responsibility for their own learning and that of their peers.

Root Cause 3: A Focus on Surface Learning Vs. Deeper Learning

How Does Surface Learning Affect Academic Achievement?

Tier 1 instruction that focuses on surface level, rapid content coverage often leaves many students behind as daily learning gaps form when students are not able to internalize the content and later recall it on a test. Although there is a lot of pressure for teachers to cover all the standards, the reality is that surface content coverage is not engaging students or sticking in their memories.

What are some signs of surface learning?

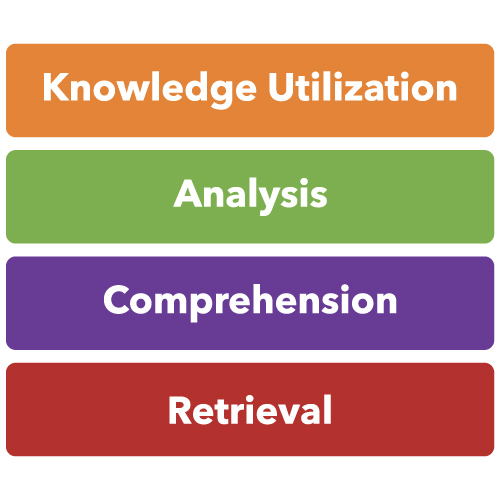

- Tasks are at the lower levels of the taxonomy – mainly retrieval, with some low rigor comprehension.

- Learning is over scaffolded with little release to allow students to engage in productive struggle.

- There is an overfocus on reteaching the standards in the grade prior, even when students only need basic review.

- The learning environment is teacher-directed, with students often disengaged, passive, and compliant.

As a result of surface learning, more and more students – particularly students who have been historically marginalized – are entering Tier 2 and 3 interventions and experiencing long-term achievement gaps that become difficult to fully close.

Closing Gaps and Increasing Student Achievement with Deeper Learning

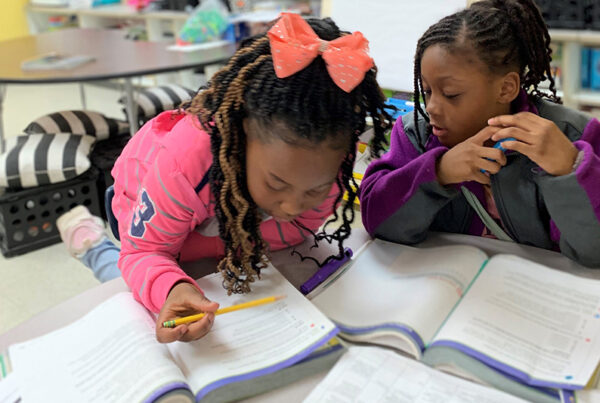

What we often forget is that teaching and student learning are distinctly different processes. While surface learning utilizes an inputs model for teaching – “If I taught it, they should learn it” – the flip to deeper learning focuses on how students are experiencing their learning. Students need processing time with student-to-student discourse in order to internalize and understand the content.

An important shift is “right-sizing” the direct instruction and moving students more quickly into an extended learning task where they lead their own learning and engage in rich academic discourse with one another. To be able to do that, students need roles, responsibilities, and norms – which are all part of the Model of Instruction for Deeper Learning.

Deeper learning sparks:

- Intrinsic motivation as students become more interested and engaged in the content through rich and lively academic discourse and tasks that bring them into the analysis and knowledge utilization taxonomy levels.

- Access to rigorous learning for all students as peers share support and perspectives (not answers) as they collaboratively unpack complex concepts.

- Memorable learning experiences that are retained through processing the content and building background knowledge, allowing students to internalize the content more deeply and ultimately perform better on achievement tests.

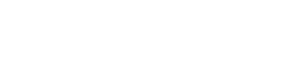

Root Cause 4: Teacher-Directed Instruction Vs. Student-Led Team Learning

How Does Teacher-Directed Instruction Affect Academic Achievement?

Most Tier 1 instruction is teacher-directed, which consists predominantly of direct instruction and independent practice activities with the students’ role in learning as passively compliant. Even if students sit together, there is usually no structure for robust collaborative learning.

Teacher-directed instruction often results in:

- Little to no rigorous and robust student-to-student discourse

- Limited use of verbal content vocabulary

- Few opportunities to articulate different viewpoints and share background knowledge with one another

- A lack of safety for more reluctant students to participate and ask for help

In teacher-directed instruction, daily learning gaps can easily compound into achievement gaps as students miss out on fully participating in rigorous learning.

Closing Gaps and Increasing Student Achievement with Student-Led Team Learning

In contrast, student-led team learning creates a leveling effect for students who might normally feel reluctant to participate in large group discussions and direct instruction. In small teams of four, students gain access to constant opportunities for robust peer discourse. They learn to respect each other and build social bonds as they work together.

Care, empathy, and belonging are very powerful components of learning that are typically not embedded in classroom instruction. But they are foundational to the Model of Instruction for Deeper Learning because when students feel a sense of belonging in their learning teams, they can more effectively access rigorous learning.

The norms and structures of student-led team learning quickly establish a classroom culture where all students feel socially and academically safe to participate. Many teachers share that they see their students come out of their shells as their reluctance starts to melt away. This is especially impactful for students who have been historically marginalized in public education and may not have experienced success in traditional teacher-directed instruction.

As students build the confidence to participate in academic discourse and tackle challenging grade level text, they thrive within their teams. Academic performance and higher achievement follow as the negative effects of opportunity gaps become less prominent in the classroom.

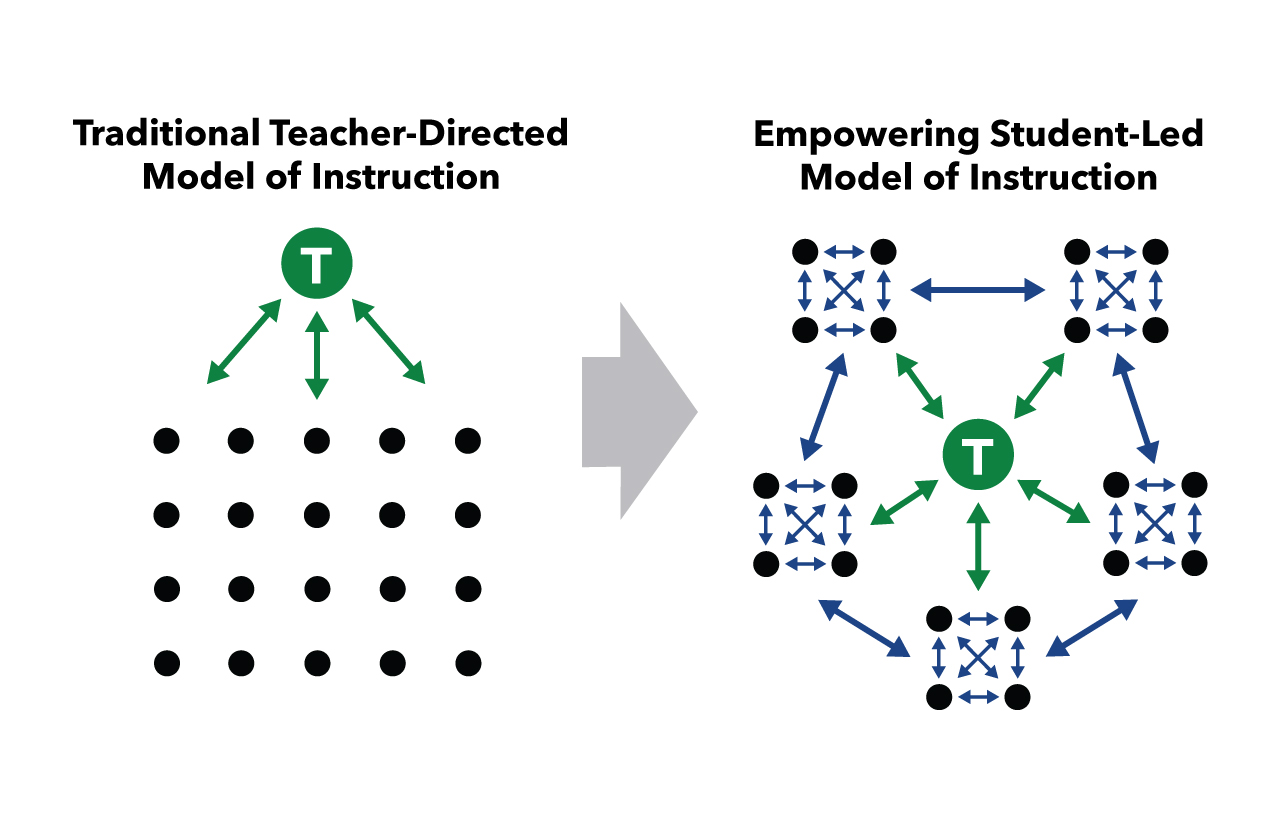

Root Cause 5: Overreliance on Tier 2 and 3 Interventions

How Does Overreliance on Tier 2 and 3 Interventions Affect Academic Achievement?

Weak Tier 1 instruction, characterized by one or more of the root causes described earlier in this article – low rigor, low engagement, surface learning, and teacher-directed – doesn’t meet the needs of all students and therefore causes more students to enter Tier 2 and Tier 3 interventions.

Furthermore, a study of data collection and analysis in Response to Intervention indicates that, although schools may collect data to screen students for the need for Tier 2 and 3 supports, this data is generally not used to inform student assignment, progress monitoring, or intervention practices (Silva et al., 2020).

Signs of overreliance on Tier 2 and 3 intervention systems include:

- More than 5% of students in Tier 3, more than 15% in Tier 2, and less than 80% in Tier 1, creating the “upside down pyramid” effect (see figure).

- Students remain in Tier 2 and 3 interventions for extended periods of time. If these interventions were working properly, we would expect to see students returned to Tier 1 within three months to a year, or moved from Tier 2 to 3 if they continue to have difficulty.

Closing Gaps and Increasing Student Achievement with Strong Tier 1 Instruction

Resolving overreliance on Tier 2 and 3 interventions requires focusing on the root cause of the problem: weak Tier 1 instruction. Redesigning Tier 1 instruction for higher rigor, engagement, and deeper learning with a student-led model allows students to master grade-level content within Tier 1, reducing the need for Tier 2 and 3 interventions.

These shifts to implementing redesigned Tier 1 instruction are critical for mitigating the negative effects of the opportunity gap and raising academic achievement. Investing time and energy into addressing the invisible root causes of low achievement will yield the lasting results that truly make a difference in the trajectory of students’ lives.

Addressing Root Causes Through Redesigned Tier 1 Instruction

Our experts have extensive experience coaching schools and districts to redesign instructional systems around a student-led model.

About the Author

Michael D. Toth is founder and CEO of Instructional Empowerment (IE) and leads IE’s Applied Research Center. He is also the author of the multi-award-winning book The Power of Student Teams with David Sousa; author of Who Moved My Standards; and co-author with Robert Marzano of multiple books. Most recently, he co-authored peer-reviewed research articles published in academic journals in collaboration with researchers Dr. Basileo, Dr. Lyons, Dr. Otto, and Dr. Vannini.

Michael is a keynote speaker at conferences and coaches and mentors superintendents on creating a bold instructional vision, designing and launching a high-functioning cabinet team, transforming Tier 1 core instruction, and leading systems-based school advancement.

Learn more about Michael: https://instructionalempowerment.com/ie-founder-michael-d-toth/

References

Bailey, D. H., Duncan, G. J., Cunha, F., Foorman, B. R., & Yeager, D. S. (2020). Persistence and fade-out of educational-intervention effects: Mechanisms and potential solutions. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 21(2), 55-97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100620915848

Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University (2024). New research shows academic recovery has started; action needed before federal spending deadline to ensure remaining gaps are closed. https://educationrecoveryscorecard.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/ERS-National-Press-Release-2024013001.pdf

de Brey, C., Musu, L., McFarland, J., Wilkinson-Flicker, S., Diliberti, M., Zhang, A., Branstetter, C., and Wang, X. (2019). Status and trends in the education of racial and ethnic groups 2018 (NCES 2019-038). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved October 10, 2024 from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2019/2019038.pdf

Dyer, K. (2015, September 17). Research proof points: Better student engagement improves student learning. NWEA. https://www.nwea.org/blog/2015/research-proof-points-better-student-engagement-improves-student-learning/

Gage, N. A., Sugai, G., Lewis, T. J., & Brzozowy, S. (2015). Academic achievement and schoolwide positive behavior supports. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 25(4), 199-209. https://doi.org/10.1177/1044207313505647

Gage, N. A., Leite, W., Childs, K., & Kincaid, D. (2017). Average treatment effect of school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports on school-level academic achievement in Florida. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 19(3), 158-167. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300717693556

Hodges, T. (2018). School engagement is more than just talk. Gallup. https://www.gallup.com/education/244022/school-engagement-talk.aspx

Kim, J., McIntosh, K., Mercer, S. H., Nese, R. N. T. (2018). Longitudinal associations between SWPBIS fidelity of implementation and behavior and academic outcomes. Behavioral Disorders, 43(3), 357-369. https://doi.org/10.1177/0198742917747589

Kraft, M.A., Edwards, D.S., & Cannata, M. (2024). The scaling dynamics and causal effects of a district-operated tutoring program (EdWorkingPaper: 24-1030). Annenberg Institute at Brown University. https://doi.org/10.26300/zcw7-4547.

Kraft, M.A., Schueler, B.E., & Falken, G. (2024). What impacts should we expect from tutoring at scale? Exploring meta-analytic generalizability (EdWorkingPaper No. 24-1031). Annenberg Institute at Brown University. https://doi.org/10.26300/zygj-m525

Marzano, R. J., & Kendall, J. S. (2007). The new taxonomy of educational objectives (2nd ed.). Corwin Press.

New York State Education Department (2010). Minimum requirements of a response to intervention program (RtI). https://nysrti.org/files/documents/resources/general/nysed_rti_guidance_document.pdf

Qu, G., Hu, W., Meng, J., Wang, X., Su, W., Liu, H., Ma, S., Sun, C., Huang, C., Lowe, S., & Sun, Y. (2023). Association between screen time and developmental and behavioral problems among children in the United States; Evidence from 2018 to 2020 NSCH. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 161, 140-149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.03.014

Silva, M. R., Collier-Meek, M. A., Codding, R. S., Kleinert, W. L., & Feinberg, A. (2020). Data collection and analysis in response-to-intervention: A survey of school psychologists. Contemporary School Psychology, 25, 554-571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-020-00280-2

Toth, M. D. & Sousa, D. A. (2019). The power of student teams: Achieving social, emotional, and cognitive learning in every classroom through academic teaming.

Talk to Our Expert Educators About Increasing Student Achievement and Closing Gaps

About IE

Our social mission is to end generational poverty and eliminate racial and socioeconomic achievement gaps through redesigned rigorous Tier 1 Instruction that develops students’ agency.