By: Meg Bowen and Michelle Fitzgerald

The effects of the pandemic have lingered for many school districts. A 2024 study by Harvard and Stanford universities examined 30 states and found:

- Only one state returned to pre-pandemic levels in math.

- Only three states returned to pre-pandemic levels in reading.

- Performance gaps between districts serving high numbers of students experiencing poverty and those serving low numbers of students experiencing poverty widened significantly during the pandemic. Recovery efforts have not closed these gaps.

As one study co-author noted, “Academic performance remains lower and more unequal than in 2019 in all but the wealthiest communities in America” (Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University, 2024).

Many districts are investing heavily in academic interventions to close gaps and are struggling to achieve desired results. While the intent behind interventions is to help students, there is a great deal of research indicating that many interventions have little impact on existing discrepancies and inequities, leaving students in the same situation year after year, perpetually behind (Steiner & Weisberg, 2020).

Below, read more about why traditional interventions often don’t work and how to use 7 instructional strategies to accelerate student learning.

Are Your Academic Interventions Catching Students Up or Leaving Them Behind?

As you review your intervention data, consider the following questions:

- What is the average length of time students are remaining in interventions (hours per day as well as days enrolled in intervention during the school year)?

- What data are you using to determine which students need interventions and on which standards the intervention focuses upon?

- Are students being pulled from core instruction for intervention?

- What does the intervention look like? Is it teacher-led? Is it a computer program?

- Are the same students participating in interventions every year?

- What percentage of students exiting interventions are demonstrating proficiency?

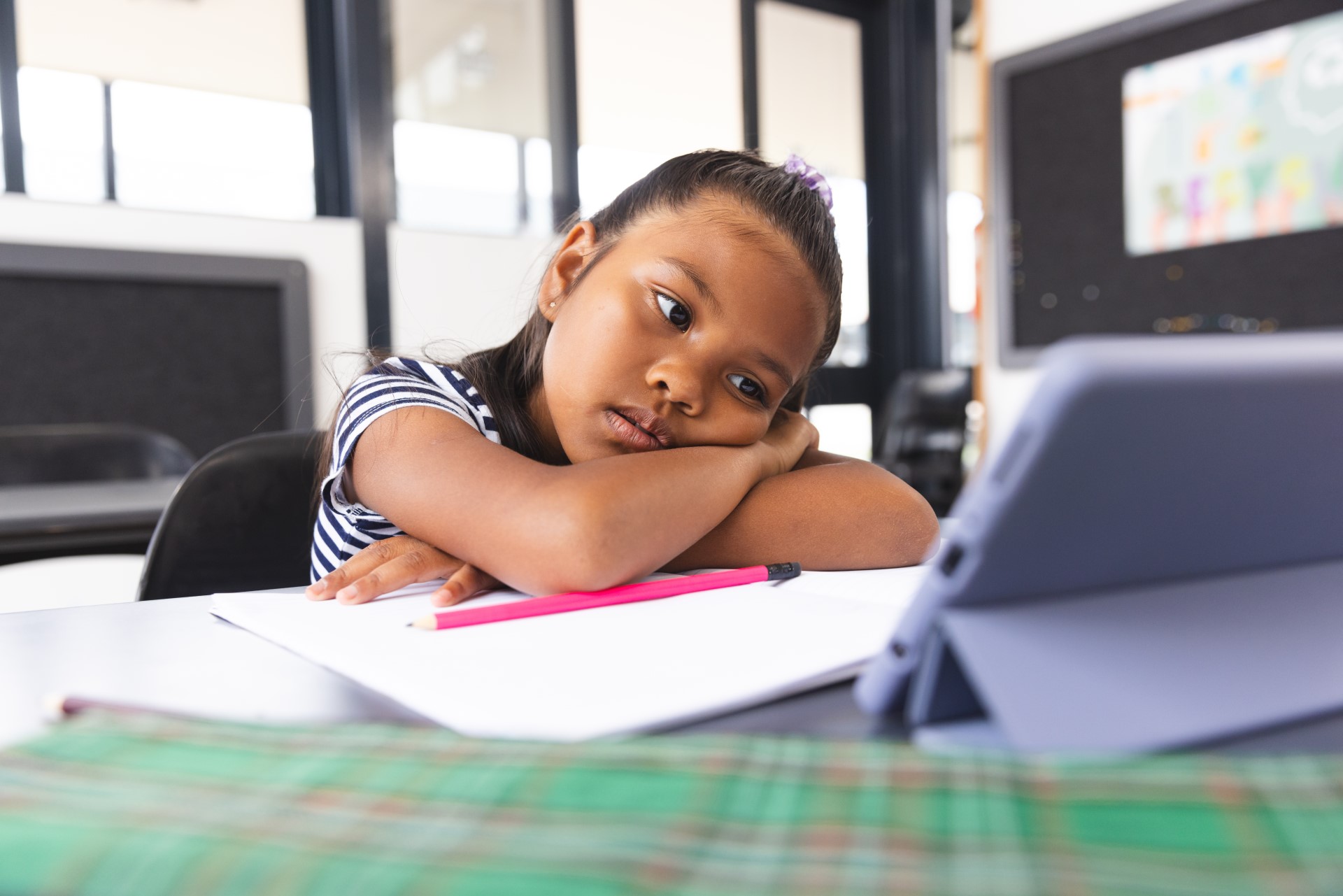

In too many cases, students remain in interventions for months or even years without any discernable results, leaving those students disengaged, discouraged, and prime candidates for dropping out. This is because they begin to expect that they will not be successful when a concept is first taught and will have to spend more time being retaught while their peers are able to move on. Those who do persevere through high school but don’t pursue a postsecondary education face an uncertain future with limited job opportunities and less earning power than peers who participate in some form of postsecondary education (Business Wire, 2011).

The best intervention is solid Tier 1 core instruction. Students who receive grade-level content throughout their school career are better prepared to successfully tackle the challenges of postsecondary education and are more likely to pursue such opportunities, which are now a necessity for attaining even modest, middle-class economic success (Achieve the Core, 2019).

In too many cases students remain in interventions for months or even years without any discernable results, leaving those students disengaged, discouraged, and prime candidates for dropping out.

Why Traditional Academic Interventions Don’t Work

Most academic interventions attempt to address broad areas of need, such as math, reading, or even reading comprehension, rather than specific skills.

Think about fifth graders who are identified as having low math proficiency. This could signify misconceptions related to place value, fractions, algebraic thinking, number sense, or a host of other key concepts.

Now imagine all the fifth graders in a given school who are lacking proficiency in math are grouped together for intervention. It’s pretty easy to see why this model doesn’t yield results; students receive general math support and practice rather than targeted instruction on the key skill or concept they need. Students do not all have the same need, even within the same grade level and subject area. Grouping them together for “one-size-fits-all” intervention is unlikely to bridge gaps. It may create frustration and disengagement in students, causing them to shut down.

The same situation happens in reading, where students who demonstrate poor reading comprehension receive the same intervention treatment regardless of whether the issue is decoding, fluency, vocabulary, or another specific area of need.

The key to accelerating rather than remediating is determining the critical skills and concepts that students are missing and providing scaffolds that will bridge gaps while teaching the missing skills with surgical precision and efficiency.

The Mastery Myth

It is easy to fall into the trap of assuming students must master all previous grade-level content before they are ready to tackle work at their current grade level.

It seems like a logical assumption, and in an ideal world, students would have the time and resources available to master previous content in an expeditious way without compromising core instructional time. Even better, learning gaps would have been prevented from ever happening as a result of skillful teacher monitoring and verification of learning.

In reality, many students do experience learning gaps and there is simply not enough time for them to go back and master all of the previous content before moving on to new content. But teachers can strategically identify the critical skills and concepts students need to fully understand grade-level content and they can teach these skills and concepts without repeating entire units or years’ worth of instruction (Rollins, 2014). When teachers are planning for instruction, they can consider the learning progression of standards and identify gaps in students’ knowledge. Then, the bridging of the gaps can occur within the instruction and not as additional intervention time for students.

The TNTP Acceleration Guide (2020) provides a great example of this strategy, where seventh-grade students who missed an entire unit on Statistics and Probability are taught the specific concept of “measures of center such as mean” because in seventh grade that concept must be applied to “…draw inferences about a random sample” (p. 9). That type of “just in time” scaffold allows students to move forward with grade-level content while bridging the gap of unfinished learning.

“Just in time” scaffolds allow students to move forward with grade-level content while bridging the gap of unfinished learning.

Bridging Gaps Vs. Filling Gaps

Bridging gaps by teaching critical skills and concepts is much more effective than attempting to fill in every hole from students’ previous learning experiences before moving on to grade-level content.

The Most Effective Ways to Accelerate Learning

There are a number of approaches to acceleration, which can be combined for maximum benefit.

During core instruction, teachers can provide scaffolds that help all students access grade-level content. Outside of core instruction, using intervention time to provide targeted instruction on specific skills or concepts gives an even bigger boost for students who have missed critical content upon which current lessons rely.

This is not the same as pre-teaching or previewing content, which is often used to help students who may lack background knowledge or need additional processing time to gain footing for upcoming lessons. In that situation, all participating students are receiving the same information, albeit in advance of the rest of the class. This one-size-fits-all approach lacks a systematic plan for diagnosing and addressing each individual student’s missing skills. For acceleration to be effective, there must be a system in place to monitor and verify learning so that critical missing skills and concepts can be identified (Steiner & Weisberg, 2020).

Regardless of the strategy, one key point is that planning is crucial in determining interventions. Teachers must be intentional in thinking through the standards to be taught in each lesson, consider the progression of standards from previous years or units, and consider how to bridge the gap – whether it be through intentional scaffolding or previewing content. Teachers should internalize every lesson, even one from a scripted curriculum resource, to be sure they have planned for every possibility of bridging the gaps for all students.

For acceleration to be effective, there must be a system in place to monitor and verify learning so that critical missing skills and concepts can be identified.

7 Instructional Strategies for Accelerating Student Learning

1 – Scaffolding Intentionally:

One of the easiest ways to accelerate is to determine the taxonomy of a lesson’s standard and learning target, and then begin instruction at a lower taxonomy level, building understanding and confidence as you gradually ramp up the rigor. Similarly, starting a lesson with less complex text to establish a solid foundation of understanding before transitioning to more complex text allows students to be successful with text that may have been inaccessible without that support. Finally, combining skills rather than focusing on isolated skills provides opportunities for students to use familiar, mastered skills in conjunction with newly acquired ones to achieve new levels of understanding.

2 – Building Knowledge and Vocabulary:

Research has shown that two factors – relevant background knowledge and vocabulary – largely determine how well students understand what they read (Fisher, n.d.). We can bolster students’ comprehension of grade-level text by building knowledge and vocabulary in a variety of ways, including immersion in multimedia resources that focus on a single topic. Systematic planned encounters with texts, photographs, recordings, and infographics that are all connected to a topic provide students with the concepts and words needed to successfully tackle challenging grade-level tasks (Wexler, 2019).

3 – Prioritizing Standards:

Not all standards are created equal, yet sometimes all are given equal instructional time. As districts continue to overcome the lingering effects of the pandemic, it is more important now than ever before to make informed, conscious decisions about how much time and attention will be devoted to specific standards. In his article on Common Core Standards, researcher Larry Ainsworth recommends evaluating standards against a list of criteria, such as:

-

- Does the standard last beyond one grade level or does it reflect a critical life skill?

- Does the standard have applications that cross over into other content areas?

- Is the standard a prerequisite for future learning?

Those standards that don’t make the cut are not eliminated; they simply are not focused upon with the same level of intensity (Ainsworth, 2015).

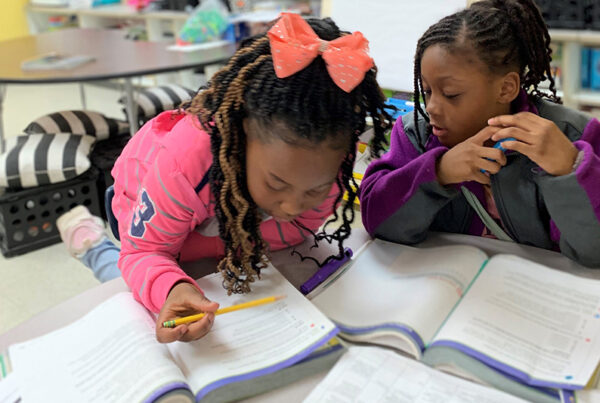

4 – Modifying Guided Reading:

In typical guided reading implementations, students work with the teacher while reading texts at their instructional level during small group time. For students whose instructional reading level matches their grade level, this is great, but what about those students who are reading several years below grade level? As noted by Steiner and Weisberg in their article about catching students up, a great deal of evidence indicates that having students continue to work in texts below grade level day after day does not help them “catch up” (Steiner & Weisberg, 2020). Instead of sticking with this model, which also often neglects to include decodable texts for young readers, spend more time working in grade-level text with appropriate scaffolding and knowledge building to ensure success.

5 – Diagnosing Essential Missed Learning:

If we don’t know which concepts and skills students are missing, how can we possibly provide the kind of targeted instruction needed to bridge those gaps? The annual high stakes test most students take isn’t likely to yield the kind of information that will help in this regard. Instead, ongoing progress monitoring is the key to uncovering areas of need that can then be addressed. It can be challenging to manage regular data collection and analysis. However, tools such as those developed by Instructional Empowerment on creating systems for real-time data monitoring as part of our Intensive Supports Partnerships builds the capacity of schools and districts to manage these processes. Instructional Empowerment’s Empower Learner Growth tool empowers students to self-assess their own learning and ask for assistance during the lesson. Teachers can verify students’ self-assessments and easily monitor the progress of the entire class from the tool’s dashboard in real time, offering “just in time” support as needed. Working with colleagues to develop a strong diagnostic measure that can be used at the beginning of each unit to determine student needs can be an additional step in monitoring students’ progress.

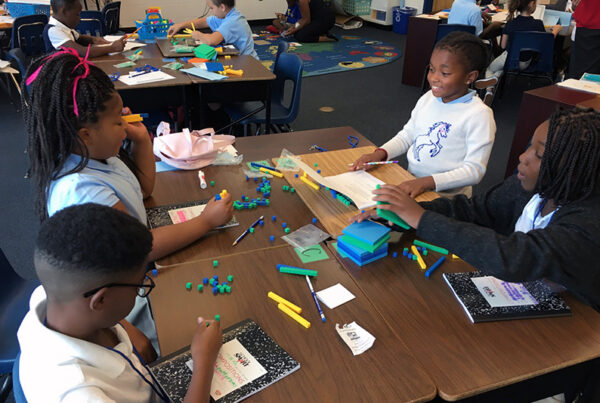

6 – Utilizing Interdependent Collaborative Student Teams:

Many classrooms and schools have achieved powerful results when students work in student-led teams to tackle rigorous, standards-based tasks. The structured student-led teams of the Model of Instruction for Deeper Learning provide opportunities for every member to contribute to the group’s success, developing essential interpersonal skills in the process. This short video shares classroom examples of students in the early stages of working in teams as they discuss how they will learn effectively together through the new structures. This second video shows a student-led team in action and demonstrates the power of the student teaming process as students push each other’s thinking without needing the teacher’s assistance. In student-led teams, each student brings different strengths to the team, making both academic and interpersonal acceleration a natural result of the collaboration (Toth & Sousa, 2019).

7 – Incorporating Text Sets:

Text sets, also called expert sets, are curated collections of multimedia resources that are tightly focused on a specific topic. How does this fit into accelerating student learning beyond the typical intervention strategies? Through the strategic use of text sets, we can prepare students to engage in discourse and tasks for which they may not otherwise have been equipped. Students can quickly get an in-depth understanding of the subject matter, including the academic vocabulary associated with the topic (Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2016).

Partnering to Accelerate Learning for All Students

Even for the most experienced educators and leaders, it can feel overwhelming to consider overhauling the traditional systems of overreliance on academic interventions and implementing more effective systems that utilize the seven instructional strategies to accelerate student learning.

Schools and districts choose to partner with Instructional Empowerment because we can support them in working through the systems that will allow for intentional bridging of gaps. Using evidence from our Applied Research Center, our Intensive Supports Partnerships are designed to help schools close persistent performance gaps, rapidly accelerate learning, and achieve long-term, sustainable gains in student achievement through:

- The Model of Instruction for Deeper Learning: We support schools in implementing student-led team learning, which is a research-based, research-proven model of instruction that builds cognitive, interpersonal, and intrapersonal skills. This model of instruction provides a structure for solid Tier 1 core instruction, which as discussed before, is the best intervention.

- Leading, Predictive Data Metrics: Our metric provides leading data on instruction – a first of its kind. This metric is highly calibrated after years of being used in tens of thousands of classrooms. Leaders can use the tool to not only predict student achievement without additional testing, but it is also correlated to student attendance, behavior, and school culture – across various groups of student demographics. In a research study, schools with score increases in the area of student-led team learning saw impacts that were even greater for students from low socioeconomic backgrounds (Basileo et al., 2024). School leadership teams can use the leading data from this tool to monitor the instruction in classrooms – looking for solid Tier 1 instruction. The data allows the leadership team to keep the focus on classroom instruction and make proactive professional learning plans immediately, preventing the need for reactive academic interventions.

- Expert Coaching: As part of our partnerships, we focus on building the capacity of school leadership teams to support the implementation of the Model of Instruction for Deeper Learning and to monitor the implementation through leading metrics. In a research study by the Applied Research Center, schools that engaged in more coaching days with Instructional Empowerment saw greater gains in student achievement (Basileo et al., 2024).

As schools and districts continue to work toward closing performance gaps, it is critical to consider the lasting effects when students spend too much time in academic interventions and remedial classes focusing on content that is years below grade level. Educators have an opportunity to change the trajectory of students by using instructional strategies that accelerate student learning and put all students on the fast track to success.

References

Achieve the Core (2019). Aligning content and practice: The design of the instructional practice guide. https://achievethecore.org/content/upload/Aligning%20Content%20and%20Practice%20-%20The%20Design%20of%20the%20Instructional%20Practice%20Guide_SAP_updated%20April%202019.pdf

Ainsworth, L. (2015). Priority standards: The power of focus. Education Week. https://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/finding_common_ground/2015/02/priority_standards_the_power_of_focus.html

Basileo, L. D., Lyons, M. E., & Toth, M. D. (2024). Leading indicators of academic achievement: Investigating the predictive validity of an observation instrument in a large district. Sage Open, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440241261119

Business Wire (2011). New study finds that earning power is increasingly tied to education; The data is clear: A college degree is critical to economic opportunity. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20110804005145/en/New-Study-Finds-That-Earning-Power-is-Increasingly-Tied-to-Education-The-Data-is-Clear-a-College-Degree-is-Critical-to-Economic-Opportunity

Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University (2024). New research shows academic recovery has started; action needed before federal spending deadline to ensure remaining gaps are closed. https://educationrecoveryscorecard.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/ERS-National-Press-Release-2024013001.pdf

Fisher, D. (n.d.). Vocabulary and background knowledge: Important factors in reading comprehension. McGraw Hill Education. https://www.mheducation.com/unitas/school/explore/sites/flex/flex-white-paper-vocabulary-background-knowledge.pdf

Rollins, S.P. (2014). Learning in the fast lane: 8 ways to put all students on the road to academic success. ASCD.

Steiner, D., & Weisberg, D. (2020). When students go back to school, too many will start the year behind. Here’s how to catch them up — in real time. The 74. https://www.the74million.org/article/steiner-weisberg-when-students-go-back-to-school-too-many-will-start-the-year-behind-heres-how-to-catch-them-up-in-real-time/

Thomas B. Fordham Institute (2016). What are “text sets,” and why use them in the classroom? https://fordhaminstitute.org/national/commentary/what-are-text-sets-and-why-use-them-classroom

TNTP (2020). Learning acceleration guide: Planning for acceleration in the 2020-2021 school year. https://tntp.org/assets/covid-19-toolkit-resources/TNTP_Learning_Acceleration_Guide.pdf

Toth, M.D., & Sousa, D.A. (2019). The power of student teams: Achieving social, emotional, and cognitive learning in every classroom through academic teaming.

Wexler, N. (2019). Elementary education has gone terribly wrong. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2019/08/the-radical-case-for-teaching-kids-stuff/592765/

Authors

Meg Bowen

Meg Bowen, M. Ed., serves as the Executive Director of Customer Experience and Growth where she works diligently to ensure districts value partnering with IE so much that they continue to collaborate with us even after they achieve their initial goals. She encourages partner schools to reach and achieve model school status, where all students are engaged in rigorous learning activities and achieve their full potential.

Michelle Fitzgerald

Michelle Fitzgerald, Ed.D., serves as the Executive Director of Advocacy and Networking for Instructional Empowerment. She has been an educator for more than 30 years and has served as an area superintendent – principal supervisor, assistant superintendent, director of curriculum, building administrator, and middle school teacher. Michelle has built instructional leadership in principals and assistant principals capitalizing on her extensive experience in curriculum, instruction, and assessment.

About IE

Our social mission is to end generational poverty and eliminate racial and socioeconomic achievement gaps through redesigned rigorous Tier 1 Instruction that develops students’ agency.