The school year has begun. The teachers excitedly enter their classrooms, getting them ready for the students who will be sharing the room with them for around 180 days. The students are excited to see which friends are in their room (and which are not), who their teacher will be, and get ready for a great year of learning. What would happen, then, if there was no plan? What if there was no GPS or roadmap for the teachers and students for their yearly journey?

The school year has begun. The teachers excitedly enter their classrooms, getting them ready for the students who will be sharing the room with them for around 180 days. The students are excited to see which friends are in their room (and which are not), who their teacher will be, and get ready for a great year of learning. What would happen, then, if there was no plan? What if there was no GPS or roadmap for the teachers and students for their yearly journey?

Without a plan for the school year, chaos might ensue. Teachers might teach different subjects at different times, leading to inconsistency in curriculum delivery. Students might lack clear expectations and goals, causing confusion and disengagement. Classroom management could become challenging as teachers struggle to maintain order without a cohesive plan.

Additionally, without a shared vision or direction, it would be difficult for the school community to work towards common goals. Teachers might have conflicting priorities, leading to frustration and inefficiency. Students might not receive the support they need to succeed academically and socially.

The importance of having a plan in any endeavor cannot be understated. Having a school improvement plan (SIP) and provides clarity and direction for everyone involved. The plan outlines specific strategies for achieving goals, ensuring that all stakeholders are on the same page. With a roadmap in place, teachers can align their instruction with the school’s objectives, and students can understand what is expected of them. This fosters a sense of unity and purpose within the school community, leading to greater success for all.

However, far too often, school improvement plans and goals are seen as a compliance task – something the be started in January of the year before and when they are complete, they are put on the shelf (or left in a virtual folder) and never referred to again. School Leadership Teams need to see the school improvement plan as a fluid document that truly provides the roadmap for the school year. But how is that done best? How can a principal guarantee the school improvement plan will be a truly active roadmap?

What if we reimagined our school improvement plans?

What if our goals truly became tied to what our students need based on our data?

What if more teachers hear their voice in our plans?

What if our plans turned into more than just a document collecting dust and instead morphed into a supercharged engine for blazing policy change and positive student outcomes?

There is a real disconnect between the purpose of a school improvement plan and its actual use. What if we reimagined goals tied to what our students truly need, with more teacher voice and supercharged for positive change?

In this article, I draw on my experience as a principal and principal supervisor to share examples of typical missteps that principals make while creating and implementing school improvement plans. I also share five critical strategies that are often missing from plans.

Principals can use these examples and strategies to reimagine school improvement plans and goals – from a chore they don’t have time for, to a planning tool that actually saves time and resources and provides a roadmap.

What the research says about school improvement plan efficacy

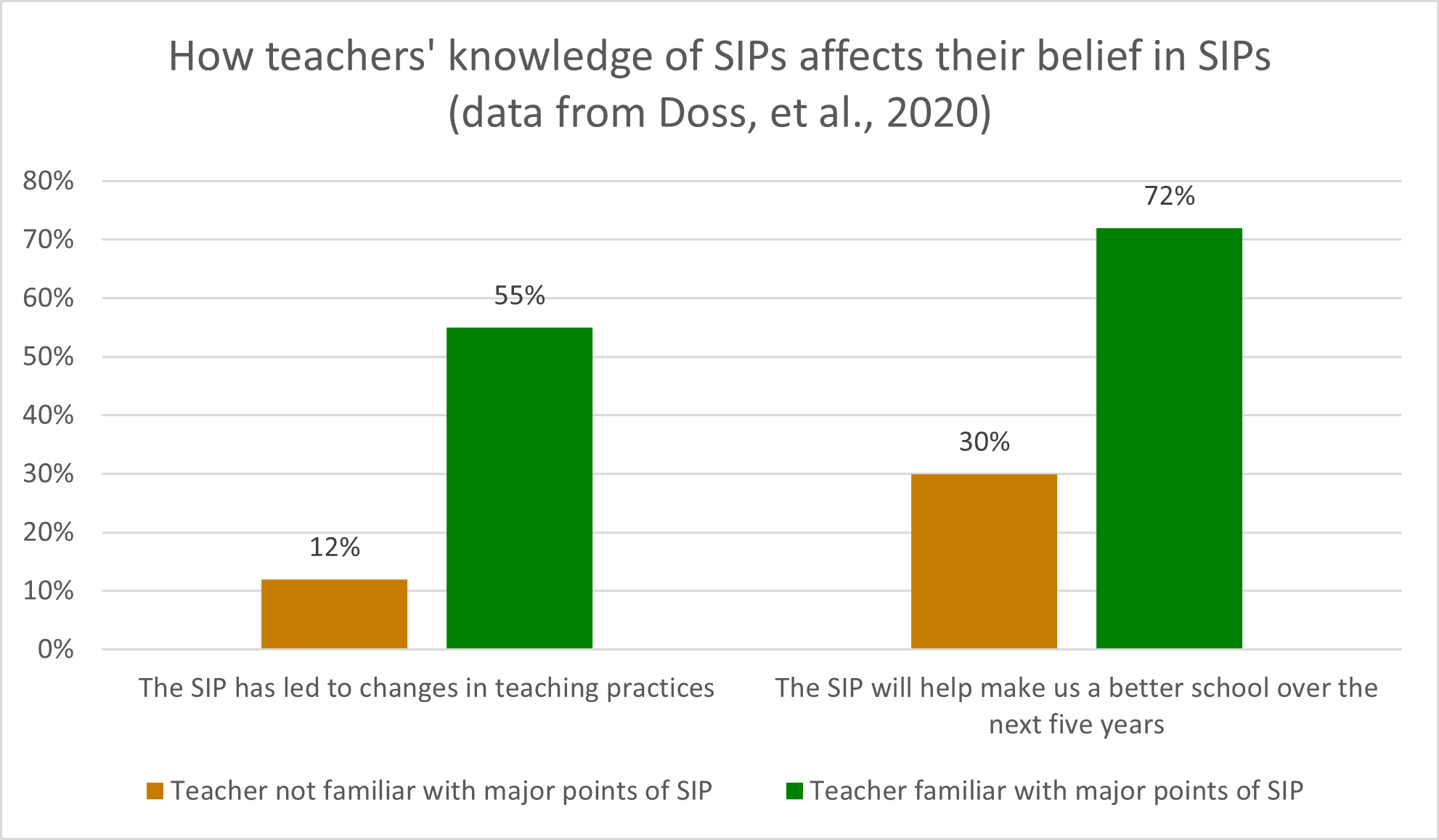

- Many educators doubt the efficacy of school improvement plans: According to a RAND survey, only 44% of teachers and 67% of principals believe school improvement plans change teaching practices. 62% of teachers and 81% of principals believed school improvement plans improve schools over a period of five years (Doss, et al., 2020).

- Teachers with more knowledge of their school’s improvement plan were more likely to believe in its effectiveness: The same RAND study found a significant disparity between how teachers felt about school improvement plans when they were familiar with the plan’s major points vs. when they were not. See figure 1 (Doss, et al., 2020).

5 Critical Strategies That Will Make a School Improvement Plan (SIP) a Dynamic Roadmap

As was highlighted earlier, there is a need to reimagine the usual process for creating and implementing school improvement plans. These have become compliance-driven acts that do not result in a dynamic roadmap. However, there is a need for the school improvement plan to be a dynamic roadmap that provides the direction of the school so all stakeholders understand the direction in which they are going. This means using new strategies to help develop the

The following five strategies are based on my work with the school improvement team at Instructional Empowerment. The Intensive Supports process is a systems-based approach where daily school improvement efforts are driven by responsibilities, metrics, goals for improvement, documented processes, and regular leadership inspection and feedback on progress to goals.

5 critical strategies missing from most school improvement plan goals:

- Distributed leadership

- Leading metrics on instruction

- Sustainable systems with documented processes

- Frequent feedback to teachers

- Daily stand-up with Action Board

1. Distribute leadership to other individuals rather than being a hero leader; engage your school leadership team.

A principal cannot do this alone. They need a solid school leadership team that is representative of all stakeholders of the school.

Shared leadership begins with shifting from a “hero leader,” where the principal takes on the burden of responsibilities by himself or herself, to empowering a team to take some of the ownership for school improvement goals. This will distribute the power to the school leadership team with clear mandates, structures, goals, and accountability.

Working with a school leadership team allows a team of teams approach, where everyone involved is empowered with responsibilities, goals, and the authority to effect positive change. When people have these responsibilities, they are more likely to see the school improvement plan as a dynamic roadmap and will follow this roadmap to school advancement. As the team is moving their work forward, they own the work and learn from it. Constantly learning from their work will result in a continuous improvement mindset.

So how do you start with shared leadership?

At a minimum, school improvement plan While the school leadership team owns the goals, you must leave the task management associated with the smaller action steps to individuals responsible. The planning process should begin months before the new school year starts.

To illustrate this strategy, consider the following goal which I will use for the duration of the discussion:

By the end of the 2021-22 school year, 65% of students will demonstrate at least one year’s growth, or learning gain, as measured by the ELA statewide assessment.

On the surface, this goal is admirable, worthy of pride as a school, and no doubt helpful toward exiting a school from any turnaround status it may be in or approaching. But it lacks clear action steps – and more importantly, clear responsibility.

When broken down to smaller action steps, an individual other than the principal becomes the owner and responsible party to see each action step through to success toward the larger goal that the whole school is pursuing together.

There is certainly more than one action step that will be connected to the larger goals, and those action steps must be owned by a responsible party. To further the example, consider the following action step:

The reading coach will facilitate subject-area planning with all ELA teachers during their common planning period on Mondays and Wednesdays focusing on improving target/task alignment during the first grading period.

In this action step, the responsible party is clearly identified, along with the task that he or she is committing to fulfill. Now we have the reading coach involved, and you’re beginning to distribute leadership to others besides yourself.

2. Use leading metrics on instruction that you can monitor and adjust to on a weekly basis rather than on a bi-annual basis

Traditional lagging data, such as state test scores, often provide limited insights for immediate instructional adjustments due to their retrospective nature. Similarly, while formative data like exit tickets and interim assessments are valuable for gauging student understanding in the moment, they’re not always utilized to their full potential for informing instructional decisions. What if we took our example and added a low-stakes, weekly metric?

Leading data on instruction offers a more proactive approach by focusing on indicators that can predict future performance and guide instructional practices in real-time. This type of data could include non-evaluative classroom observations, real-time student engagement metrics, real-time progress on learning objectives, and examining student actions and student work in the moment.

To leverage leading data effectively in school improvement plans and instructional practices, schools can consider the following strategies:

- Collect and Analyze Real-Time Data: Encourage teachers to regularly collect and analyze leading data on instruction to identify trends, strengths, and areas for improvement. This could involve using digital tools for non-evaluative classroom observations, tracking student participation and engagement, and analyzing ongoing assessment data.

- Embed Leading Data in School Improvement Plans: Incorporate leading data indicators into the school improvement planning process to inform goals, strategies, and action steps. This could involve setting targets for specific instructional practices or student engagement metrics and monitoring progress over time.

- Provide Professional Learning: Offer professional learning opportunities for teachers to strengthen their capacity to collect, analyze, and use leading data effectively. This could include training on data-informed instruction, formative assessment practices, and instructional strategies proven to impact student learning.

- Promote Data-Driven Decision Making: Foster a culture of data-driven decision-making at all levels of the school community, where teachers, administrators, and other stakeholders regularly collaborate to analyze data, share insights, and make informed adjustments to instruction and support initiatives.

- Monitor Implementation and Impact: Continuously monitor the implementation and impact of instructional practices informed by leading data to assess effectiveness and identify areas for refinement. This could involve ongoing reflection, feedback mechanisms, and adjustments based on evidence of what works best for students.

By prioritizing leading data on instruction and integrating it into school improvement plans and instructional practices, schools can take a more proactive and targeted approach to supporting student learning and achievement.

What if we took our example and added a low-stakes, weekly metric?

The reading coach will facilitate subject-area planning with all ELA teachers during their common planning period on Mondays and Wednesdays focusing on improving target/task alignment during the first grading period. During classroom walkthroughs, the reading coach will measure target/task alignment using a research-based classroom walkthrough tool, such She will specifically identify the taxonomy level of the lesson learning target and the taxonomy level of the student work being produced and track whether the levels are aligned. Each teacher will demonstrate target/task alignment in three out of four weekly classroom visits as measured by the walkthrough tool.

Now, not only do we have a specific task and person responsible, but also we have a metric (in this example, Rigor Classroom Walk) and a goal for incremental improvement (target/task alignment in three out of four weekly classroom visits) which rolls up to the larger goal of 65% learning gains in ELA.

The distribution of our school improvement work has grown from the reading coach to now include all ELA teachers. The wave of ownership is building!

3. Build sustainable systems with documented processes rather than relying on talented individuals

Systems are crucial in the running of a school. Often, when a school is not performing where they want to be performing, it is because systems are misaligned. Once the systems are defined, the leadership team needs to determine where they are in each of the systems from misaligned to highly functional and they need to determine the processes to put into place that become a way of work and achieve sustainable success.

Let’s revisit our annual goal example quickly so we don’t lose sight of what we are trying to accomplish:

By the end of the 2021-22 school year, 65% of students will demonstrate at least one year’s growth, or learning gain, as measured by the ELA statewide assessment.

We can’t simply off-load tasks and responsibilities to the reading coach and ELA teachers and think everything is going to be okay. Don’t stop there!

If true, sustainable school improvement is what we desire, we must develop mature systems – systems that can succeed regardless of the individual.

A documented process is critical: a process that can be picked up, utilized, refined, and passed on to ensure success continues. Using our example, the documented process for the reading coach would include:

- Weekly coaching calendars

- PLC agendas

- Sample student work products

- Instructions related to classroom walkthroughs

- How to use the Rigor Classroom Walk (or whichever tool she is using) to capture target/task alignment data

- Suggested ways to share the data

- How to use the data collected to inform next steps in the PLC process

When teams create a documented process, it results in high ownership and reduces the risk of failure to attain system goals because it isn’t dependent on a single person. The power is in the process.

Now we have the reading coach, ELA teachers, and anyone else who might join the team on equal footing. New teacher? New reading coach? Veteran teacher? Veteran reading coach? District reading specialist? It doesn’t matter. The process supports everyone.

Distributed systems for school improvement mean creating documented processes that any person can use, refine, and pass on. Even as the team adds or loses members over time, the hard work of improving student outcomes continues

4. Inspect classrooms regularly and provide meaningful feedback to teachers

In the pursuit of school improvement plan goals, the principal’s most critical functions are regular non-evaluative classroom observations, meaningful feedback to teachers on their instruction, and feedback on progress toward the goals.

When these responsibilities become the principal’s focus, schools experience the highest levels of ownership, most reliable results, and lowest risk of failure to attain system performance goals.

Think back to all of the research and discussions over the years about the need for the principal to be the instructional leader of the school (e.g., Lunenburg, 2010). This is how it’s done.

So far, we have focused on one example goal from our school improvement plan: achieving 65% learning gains as measured by the ELA statewide assessment. We should now break our annual goals down into 45-day goals and make them visible for everyone. For example:

By October 15, 80% of teachers will provide students with tasks that are aligned to grade-level standards as measured by classroom walkthrough data.

This 45-day goal is then displayed on the school’s action board. An action board is a visible tool that provides urgency and focus, guiding the school leadership team (SLT) in implementing and monitoring the systems that lead to the vision of transformed student achievement.

The action board provides a clear focus on how the SLT members should spend their time. Action boards allow leadership teams to take their 45-day goals and break them down into two-week “sprints,” where action steps move through columns titled “To Do,” “Doing,” and “Done.”

The action steps on an action board are not a “to do” list in the traditional sense. They are connected to specific actions that individual members of the SLT own, which are all connected to the school improvement plan goals. Any miscellaneous or operational items that members of the SLT need to get done (for example, creating a fire drill plan) do NOT go on the action board.

An action step is considered “done” when it meets specific criteria connected to the metrics we identified earlier (in our example, the number of classrooms that demonstrated target/task alignment as measured by the Classroom Rigor Walk). If the action step does not meet the criteria, it cannot be considered “done.” It is the principal’s role to inspect evidence of “done” and provide feedback.

Let’s take a look at an example that includes two action steps from the reading coach with one definition of done that requires leadership (principal) inspection:

- Action Steps

- The reading coach will attend and participate in Grade 4 ELA PLCs on Monday and Wednesday, focusing on Target/Task Alignment.

- The reading coach will conduct a classroom walkthrough for each Grade 4 ELA teacher and provide feedback on Target/Task Alignment.

- Definition of Done

- The principal will visit all 5 ELA teachers during their ELA block on Friday. In 4 out of 5 classrooms, the observed learning target and task will be aligned at the appropriate taxonomy or higher as measured by the Classroom Walk.

Notice how throughout these examples, our annual goal has transitioned to a 45-day goal, then to specific action steps that the reading coach owns, to teachers getting consistent and documented feedback directly connected to action steps, to the principal verifying through leadership inspection.

The throughline here is powerful! Imagine the support the reading coach and teachers are feeling knowing that their principal is also invested in the outcome. That ownership wave just grew another 10 feet!

5. Lead your team towards continuous improvement with daily stand-ups around an action board

The final strategy that brings shared leadership together is regular feedback on the team’s progress and efficacy at meeting the school improvement plan goals.

Like leadership inspection of the action steps, the principal owns this critical process.

At the heart of the continuous improvement process is the daily stand-up. A daily stand-up is when members of the school leadership team (SLT) gather around the action board as the principal leads 5 to 15 minutes of discussion. The daily stand-up happens at the same time each day and in the same location even if all members of the SLT are not present at school that day. This time is always consistent and protected.

During the daily stand-up, the principal asks each member of the SLT what he or she completed the previous day that is moving us toward meeting our goals.

It is not a rundown of what each member did or did not do; the focus is on specific actions (the ones on the action board) and outcomes from the classroom that will lead to meeting the goal by the end of the week.

After each person identifies what they were able to accomplish, the conversation turns to any impediments to meeting the goal for the week. The SLT then works to solve the impediments, so they are not continuously holding the team back. The SLT holds each other accountable for meeting the goals.

Data is central to all discussions. The game plan for tomorrow is also cemented. No more annual, quarterly, monthly, or weekly focus on where we are as a school. Now you know on a daily basis.

What results can you expect after using the 5 strategies?

So, what does it look like when a school fully commits to the five strategies described above?

Instructional Empowerment has partnered with many public schools to implement these strategies. You can find the powerful results in our .

In our partner schools, the improvement process becomes a system owned by everyone, not just a select few – and in the end, students have benefitted immensely.

By embracing shared responsibilities, weekly progress metrics, documented processes, regular leadership inspection, and daily feedback on goals for improvement, principals have empowered the entire school.

Don’t you want to be a part of a school like this?

References

Doss, C.J., Akinniranye, G., Tosh, K. (2020). School improvement plans: Is there room for improvement? RAND Corporation. https://doi.org/10.7249/RR2575.4-1

Lunenburg, F.C. (2010). The principal as instructional leader. National Forum of Educational Supervision Journal, 27(4). http://www.nationalforum.com/Electronic%20Journal%20Volumes/Lunenburg,%20Fred%20C.%20The%20Principal%20as%20Instructional%20Leader%20NFEASJ%20V27%20N4%202010.pdf

About the Author: Michelle Fitzgerald

Dr. Michelle Fitzgerald is an Instructional Empowerment expert educator and the Executive Director of School Advancement. Michelle and her colleague, Dr. Lindsay Elliott, work with schools across the country, supervising our field faculty and ensuring each project’s success.

Michelle has been an educator for more than 30 years. During that time, she has served as area superintendent – principal supervisor, assistant superintendent, director of curriculum, building administrator, and middle school teacher. She has experience with standards-based curriculum development, best practices in instructional delivery, and assessment with a focus on data-driven instruction. Michelle built instructional leadership in principals and assistant principals capitalizing on her extensive experience in curriculum, instruction, and assessment.